|

Making repeated separations

of the various substances in the pitchblende, Marie and Pierre used

the Curie electrometer to identify the most radioactive fractions.

They thus discovered that two fractions, one containing mostly bismuth

and the other containing mostly barium, were strongly radioactive.

In July 1898 the Curies published their conclusion: the bismuth

fraction contained a new element. Chemically it acted almost exactly

like bismuth, but since it was radioactive, it had to be something

new. They named it "polonium" in honor of the country of Marie's

birth. A second publication, in December

1898, explained their discovery in the barium fraction of another

new element, which they named "radium" from the Latin word for ray.

The Curies were close to reaching one of the highest goals that

a scientist of the time could hope to achieve--placing new elements

in the Periodic Table. While the chemical

properties of the two new elements were completely dissimilar, they

both had strong radioactivity.

|

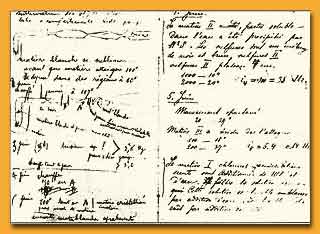

A page from the Curies' lab notebook of

1898. On the left, in Pierre's hand, a sublimation procedure.

On the right, in Marie's hand, chemical processing. (Photo

ACJC) Another

picture

Read the Discovery

Paper in which the Curies announced the existence of Radium...

|

O

CONVINCE THE SCIENTIFIC COMMUNITY of the existence of polonium

and radium, and to complete the identification and establish the

nature of the new elements, Marie set out to isolate them from the

bismuth and barium with which they were mixed. Since the Municipal

School storeroom would be inadequate to the task, the Curies moved

their lab to an abandoned shed across the school courtyard. The

shed, formerly a medical school dissecting room, was poorly outfitted

and ventilated. It was not weathertight. She succeeded in separating

the radium from the barium only with tremendous difficulty -- which

would become central in the romantic legend

of her life. She had to treat very large quantities of pitchblende,

a ton of which the Curies received as a donation from the Austrian

government. (The Austrians hoped she would find a use for a mineral

their mines yielded as a waste byproduct.) O

CONVINCE THE SCIENTIFIC COMMUNITY of the existence of polonium

and radium, and to complete the identification and establish the

nature of the new elements, Marie set out to isolate them from the

bismuth and barium with which they were mixed. Since the Municipal

School storeroom would be inadequate to the task, the Curies moved

their lab to an abandoned shed across the school courtyard. The

shed, formerly a medical school dissecting room, was poorly outfitted

and ventilated. It was not weathertight. She succeeded in separating

the radium from the barium only with tremendous difficulty -- which

would become central in the romantic legend

of her life. She had to treat very large quantities of pitchblende,

a ton of which the Curies received as a donation from the Austrian

government. (The Austrians hoped she would find a use for a mineral

their mines yielded as a waste byproduct.)

Luckily some help

was available for the tedious labor of treating the pitchblende.

They were able to collaborate with the Central Chemical Products

Company, the firm that marketed Pierre's scientific instruments.

Their colleague André Debierne cleverly adapted their standard lab

techniques into larger-scale industrial processes. These processes

isolated from the pitchblende materials with high concentrations

of radium and polonium, which the Curies studied in detail in what

she called the “miserable old shed.” In exchange for supplying

chemical products and paying staff wages, the Central Chemical Products

Company took a share of the radium salts extracted on its premises.

The firm would later make a handsome profit by marketing these radium

salts for medical and other uses.

Despite the industrial

assistance the Curies received, it took Marie over three years to

isolate one tenth of a gram of pure radium chloride. For reasons

that would not be fully understood until the concept of radioactive

decay was developed, Marie never succeeded in isolating polonium,

which has a half-life of only 138 days.

� 2000

-

American Institute of Physics |