|

In addition, remaining

with the Dluskis meant participating regularly in the active Polish

exile community in Paris. Marie's father warned her that doing

so might jeopardize her career prospects at home or even the lives

of relatives there. Thus after a few months Marie moved to the

Latin Quarter, the artists' and students' neighborhood close to

the university.

|

|

Her living arrangements

were basic. Stories from these years tell how she kept herself

warm during the winter months by wearing every piece of clothing

she owned, and how she fainted from hunger because she was too

absorbed in study to eat. But even if Bronya had to come to her

aid from time to time, living alone enabled Marie to focus seriously

on her studies.

“...my

situation was not exceptional; it was the familiar experience

of many of the Polish students whom I knew....”

|

|

Paris rooftops, painting by Gustave Caillebotte

[More]

|

|

HE HAD A LOT OF

CATCHING UP to do. Marie realized quickly that her fears of

being insufficiently prepared were accurate. Neither her math and

science background nor her proficiency in technical French equaled

that of her fellow students. Refusing to lose heart, she determined

to overcome these shortcomings through diligent work.

HE HAD A LOT OF

CATCHING UP to do. Marie realized quickly that her fears of

being insufficiently prepared were accurate. Neither her math and

science background nor her proficiency in technical French equaled

that of her fellow students. Refusing to lose heart, she determined

to overcome these shortcomings through diligent work. |

|

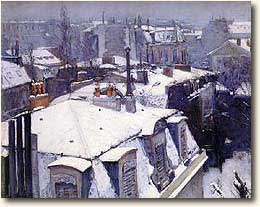

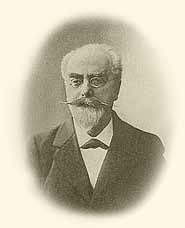

| Another Polish student in Paris drew this

portrait of Marie in 1892, after she had been enrolled at

the Sorbonne for some months. Although at first she spent

some time with other Polish students to help overcome homesickness,

she soon had to devote all her time to her studies. (Photo

ACJC) |

|

The diligence paid

off. Marie finished first in her master's degree physics course

in the summer of 1893 and second in math the following year. Lack

of money had stood in the way of her undertaking the math degree,

but senior French scientists recognized her abilities and pulled

some strings. She was awarded a scholarship earmarked for an outstanding

Polish student. Before completing the math degree she was also

commissioned by the Society for the Encouragement of National

Industry to do a study, relating magnetic properties of different

steels to their chemical composition. She needed to find a lab

where she could do the work.

Love

and Marriage

Love

and Marriage

HE SEARCH FOR

LAB SPACE led

to a fateful introduction. In the spring of 1894, Marie Sklodowska

mentioned her need for a lab to a Polish physicist of her acquaintance.

It occurred to him that his colleague Pierre

Curie might be able to assist her. Curie, who had done pioneering

research on magnetism, was laboratory chief at the Municipal School

of Industrial Physics and Chemistry in Paris. Unaware of how inadequate

Pierre's own lab facilities were, the professor suggested that

perhaps Pierre could find room there for Marie to work. The meeting

between Curie and Sklodowska would change not only their individual

lives but also the course of science.

HE SEARCH FOR

LAB SPACE led

to a fateful introduction. In the spring of 1894, Marie Sklodowska

mentioned her need for a lab to a Polish physicist of her acquaintance.

It occurred to him that his colleague Pierre

Curie might be able to assist her. Curie, who had done pioneering

research on magnetism, was laboratory chief at the Municipal School

of Industrial Physics and Chemistry in Paris. Unaware of how inadequate

Pierre's own lab facilities were, the professor suggested that

perhaps Pierre could find room there for Marie to work. The meeting

between Curie and Sklodowska would change not only their individual

lives but also the course of science.

|

“I noticed the grave and gentle expression

of his face, as well as a certain abandon in his attitude, suggesting

the dreamer absorbed in his reflections.”

|

|

Marie would eventually

find rudimentary lab space at the Municipal School. Meanwhile

her relationship with Curie was growing from mutual respect to

love. Her senior by about a decade, Pierre had all but given up

on love after the death of a close woman companion some 15 years

earlier. The women he had met since had shown no interest in science,

his life's passion. In Marie, however, he found an equal with

a comparable devotion to science.

OLAND

STILL BECKONED HER BACK. After her success in her math exam

in the summer of 1894, Marie returned there for a vacation, uncertain

whether she would return to France. Pierre's heartfelt letters

helped convince her to pursue her doctorate in Paris. OLAND

STILL BECKONED HER BACK. After her success in her math exam

in the summer of 1894, Marie returned there for a vacation, uncertain

whether she would return to France. Pierre's heartfelt letters

helped convince her to pursue her doctorate in Paris.

|

|

|

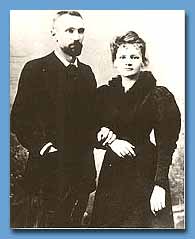

Marie hesitated before agreeing to marry

Pierre Curie, because such a decision

“meant abandoning my country and my family.” (Photo

ACJC)

READ

Curie's words

|

|

|

| Gabriel Lippmann, Marie Curie's thesis

advisor, did early studies in a field in which Pierre

Curie and his brother were pioneers: electrical effects

in crystals. A pillar of the French tradition of patronage,

Lippmann let Marie use his laboratory for her thesis

work and helped her find other sources of support. |

|

“Our work drew us closer and closer, until we were

both convinced that neither of us could find a better

life companion.”

Marie was determined

not only to get her own doctorate but to see to it that Pierre

received one as well. Although Pierre had done important scientific

research in more than one field over the past 15 years, he

had never completed a doctorate (in France the process consumed

even more time than it did in the U.S. or U.K.). Marie insisted

now that he write up his research on magnetism. In March 1895

he was awarded the degree. At the Municipal School Pierre

was promoted to a professorship. The honor and the higher

salary were offset by increased teaching duties without any

improvement in lab space. |

|

|

In a simple civil

ceremony in July 1895, they became husband and wife. Neither wanted

a religious service. Marie had lost her faith when her devout

Roman Catholic mother died young, and Pierre was the son of non-practicing

Protestants. Nor did they exchange rings. Instead of a bridal

gown Marie wore a dark blue outfit, which for years after was

a serviceable lab garment.

|

|

The Curies' honeymoon trip was a tour of

France on bicycles purchased with a wedding gift. (Photo ACJC)

Another view |

|

|