|

Honors from Abroad

Honors from Abroad

RANCE

WAS LESS FORTHCOMING than other countries when it came to honoring

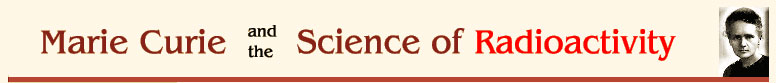

the Curies' work. In early June 1903 both Curies were invited to

London as guests of the prestigious Royal Institution. Since custom

ruled out women lecturers, Pierre alone described their work in

his “Friday Evening Discourse.” He was careful, however,

to describe Marie's crucial role in their collaboration. The audience

included representatives of England's social elite and such major

scientists as Lord Kelvin. Kelvin showed his respect by sitting

next to Marie at the lecture and by hosting a luncheon in Pierre's

honor the following day. RANCE

WAS LESS FORTHCOMING than other countries when it came to honoring

the Curies' work. In early June 1903 both Curies were invited to

London as guests of the prestigious Royal Institution. Since custom

ruled out women lecturers, Pierre alone described their work in

his “Friday Evening Discourse.” He was careful, however,

to describe Marie's crucial role in their collaboration. The audience

included representatives of England's social elite and such major

scientists as Lord Kelvin. Kelvin showed his respect by sitting

next to Marie at the lecture and by hosting a luncheon in Pierre's

honor the following day.

|

|

| Britain's Lord Kelvin, whose contributions

in several fields helped shape the scientific thought of his

era, openly displayed his admiration for Pierre's scientific

achievements. |

|

|

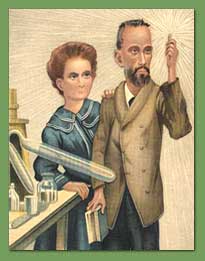

| The attention that English

scientists paid to the Curies' work helped make them household

names in that country, as in this famous caricature, “Radium,”

from the popular British periodical Vanity Fair. |

|

But all was not well

that weekend. Pierre was in such bad health that he had experienced

difficulty in dressing himself before the talk. His fingers were

so covered with sores that he spilled some radium in the hall while

demonstrating its properties. Ill health, however, kept neither

Curie from noting the value of the jewels worn by the members of

English high society they met in the course of the weekend. They

amused themselves by estimating the number of fine laboratories

they could set up with the proceeds from selling those jewels.

ISITORS

FROM ABROAD also helped honor Marie on the occasion of her formal

thesis defense in June 1903. Her sister Bronya made the difficult

trip from Poland to celebrate Marie's academic triumph. ISITORS

FROM ABROAD also helped honor Marie on the occasion of her formal

thesis defense in June 1903. Her sister Bronya made the difficult

trip from Poland to celebrate Marie's academic triumph.

Bronya had insisted that the first woman to receive a doctorate in

France should acknowledge the special event by wearing a new dress.

Characteristically, Marie chose a black dress. Like the navy wedding

outfit she had chosen eight years earlier, the new dress could be

worn in the lab without fear of stains. |

|

| Title page of the published version of Marie

Curie's doctoral thesis, “Research on Radioactive Substances.”

The examiners exclaimed that Curie's doctoral research contributed

more to scientific knowledge than any previous thesis project. |

|

Another foreign admirer

was a last-minute guest at a dinner to celebrate Marie's achievement.

New Zealand-born scientist Ernest Rutherford, who was also actively

engaged in research in the new science of radioactivity, was visiting

Paris. He had stopped by the Municipal School shed where Marie isolated

radium, and at dinner that night he asked Marie how they managed

to work in such a place. “You know,” he said, “it

must be dreadful not to have a laboratory to play around in.”

AMILY

LOSSES UNDERCUT some of the pleasure Marie could take in her

own achievements. In August 1903 she experienced a miscarriage.

Some time later Bronya's second child died of tubercular meningitis.

And against the backdrop of these specific losses was the fact that

Pierre's health continued to deteriorate. Sometimes unbearable pain

kept him awake all night, lying weakly in bed, moaning. AMILY

LOSSES UNDERCUT some of the pleasure Marie could take in her

own achievements. In August 1903 she experienced a miscarriage.

Some time later Bronya's second child died of tubercular meningitis.

And against the backdrop of these specific losses was the fact that

Pierre's health continued to deteriorate. Sometimes unbearable pain

kept him awake all night, lying weakly in bed, moaning.

|

“I

had grown so accustomed to the idea of the child that I am absolutely

desperate and cannot be consoled.”

--letter from Marie Curie to Bronya, August 25, 1903

|

|

|

| Marie Curie in 1903, the

year her thesis was published. (Photo ACJC) |

|

|

� 2000 -

American Institute of Physics

|

|