Introduction and Summary:

A Hyperlinked History of Climate Change Science

"To a patient scientist, the unfolding

greenhouse mystery is far more exciting than the plot of the best

mystery novel. But it is slow reading, with new clues sometimes not

appearing for several years. Impatience increases when one realizes

that it is not the fate of some fictional character, but of our planet

and species, which hangs in the balance as the

great carbon mystery unfolds at a seemingly glacial

pace."

— D. Schindler, 1999(1)

It is an epic story: the struggle of thousands of men and women over the course of a century for very high stakes. For some, the work required actual physical courage, a risk to life and limb in icy wastes or on the high seas. The rest needed more subtle forms of courage. They gambled decades of arduous effort on the chance of a useful discovery, and staked their reputations on what they claimed to have found. Even as they stretched their minds to the limit on intellectual problems that often proved insoluble, their attention was diverted into grueling administrative struggles to win minimal support for the great work. A few took the battle into the public arena, often getting more blame than praise; most labored to the end of their lives in obscurity. In the end they did win their goal, which was simply knowledge.

The scientists who labored to understand Earth's climate discovered that many factors influence it. Everything from volcanoes to factories shape our winds and rains. The scientific research itself was shaped by many influences, from popular misconceptions to government funding, all happening at once. A traditional history would try to squeeze the story into a linear text, one event following another like beads on a string. Inevitably some parts are left out. Yet for this sort of subject we need total history, including all the players — mathematicians and biologists, lab technicians and government bureaucrats, industrialists and politicians, newspaper reporters and the ordinary citizen. This website is an experiment in a new way to tell a historical story. Think of the site as an object like a sculpture or a building. You walk around, looking from this angle and that. In your head you are putting together a rounded representation, even if you don't take the time to inspect every cranny. That is the way we usually learn about anything complex.

You can start with the following 10-minute overview. Or skip down to advice on using this site. This and all other files are available in a printable format (but you'll miss the hyperlinks and the most recent updates).

The story in a nutshell: Like most histories, this one begins far back. People had long suspected that human activity could change the local climate. For example, ancient Greeks and 19th-century Americans debated how cutting down forests might bring more rainfall to a region, or perhaps less. But greater shifts of climate happened all by themselves. The discovery in the mid 19th century that there had been ice ages in the distant past proved that climate could change radically over much of the globe, a change vastly beyond anything mere humans seemed able to cause. So what did cause global climate change — was it variations in the heat of the Sun? Volcanoes erupting clouds of smoke? The raising and lowering of mountain ranges, which diverted wind patterns and ocean currents? Or could it be changes in the composition of the air itself? In 1824 a French scientist had explained that Earth's temperature would be much lower if the planet lacked an atmosphere, and in 1859 an English scientist discovered that the chief gases that trapped heat were water vapor and carbon dioxide (CO2).

In 1896 the Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius published a new idea. By burning fossil fuels such as coal, thus adding CO2 to Earth's atmosphere, humanity would raise the planet's average temperature. This "greenhouse effect," as it later came to be called, was only one of many speculations about climate change, and not the most plausible. The few scientists who paid attention to Arrhenius used clumsy experiments and rough approximations to argue that our emissions could not change the planet. Most people thought it was already obvious that puny humanity could never affect the vast global climate cycles, which were governed by a benign "balance of nature."

In the 1930s, measurements showed that the United States and North Atlantic region had warmed significantly during the previous half-century. Scientists supposed this was just a phase of some mild natural cycle, probably regional, with unknown causes. Only one lone voice, the English steam engineer and amateur scientist Guy Stewart Callendar, published arguments that greenhouse warming was underway. If so, he and most others thought it would be beneficial.

In the 1950s, Callendar's claims provoked a few scientists to look into the question with far better techniques and calculations than earlier generations could have deployed. This research was made possible by a sharp increase of government funding, especially from military agencies that wanted to know more about the weather and geophysics in general. Not only might such knowledge be crucial in future battles, but scientific progress could bring a nation prestige in the Cold War competition. The new studies showed that, contrary to earlier crude assumptions, CO2 might indeed build up in the atmosphere and bring warming. In 1960 painstaking measurements of the level of the gas in the atmosphere by Charles Keeling, a young scientist with an obsession for accuracy, drove home the point. The level was in fact rising year by year.

During the next decade a few scientists worked up simple mathematical models of the planet's climate system and turned up feedbacks that could make the system surprisingly sensitive. Others figured out ingenious ways to retrieve past temperatures by studying ancient pollen and fossil shells. It appeared that grave climate change could happen, and in the past had happened, within as little as a century or two. This finding was reinforced by more elaborate models of the general circulation of the atmosphere, an offshoot of a government-funded effort to use the new digital computers to predict (and perhaps even deliberately change) the weather. Calculations made in the late 1960s suggested that in the next century, as CO2 built up in the atmosphere, average temperatures would rise a few degrees. But the models were preliminary, and the 21st century seemed far away.

In the early 1970s, the rise of environmentalism raised public doubts about the benefits of any human activity for the planet. Curiosity about climate change turned into anxious concern. A few degrees of warming no longer sounded benign, and as scientists looked into possible impacts they noticed alarming possibilities of rising sea levels and possible damage to agriculture.

Meanwhile a few scientists pointed out that human activity was putting not only CO2 but ever more dust and smog particles into the atmosphere, where they could block sunlight and cool the world. Analysis of Northern Hemisphere weather statistics showed that a cooling trend had begun in the 1940s; was pollution the cause? (Decades later, scientists would confirm that soaring industrial pollution had in fact contributed to temporary Northern Hemisphere cooling.) The public media were confused, sometimes predicting a balmy globe with coastal areas flooded as the ice caps melted, sometimes foreboding a catastrophic new ice age, sometimes quoting expert reassurances that nothing much would change. Study panels of scientists, first in the U.S. and then internationally, began to warn that one or another kind of future climate change might pose a severe threat. The main thing scientists agreed on was that they scarcely understood the climate system. The only policy action they recommended was to fund more research to find out what might really happen. Research activity did accelerate using state-of-the-art computers, international programs to assemble weather data, and adventurous expeditions across oceans and ice caps to gather information on past climates.

Most scientists thought a disastrous cooling was unlikely, if only because dust and smog fall out of the atmosphere in weeks, whereas CO2 would linger for centuries. Computer models, improving at the breakneck pace of computing in general, consistently showed warming. With worries about climate change rising, in 1979 the U.S. National Academy of Sciences convened a committee of experts to hash out what could reliably be said. They reached a consensus that when CO2 reached double the pre-industrial level, sometime in the following century, the planet would probably warm up by about 3°C (5.4°F), plus or minus a degree or two.

Earlier scientists had sought a single master-key to climate, but now they were coming to understand that climate is an intricate system responding to a great many influences. Volcanic eruptions and solar variations were still plausible causes of change, and some argued these would swamp any effects of human activities. Even subtle changes in the Earth's orbit could make a difference. To the surprise of many, studies of ancient climates showed that astronomical cycles had partly set the timing of the ice ages. Apparently the climate was so delicately balanced that almost any small perturbation might set off a large shift. According to the new "chaos" theories, in a complex system a shift might happen suddenly. Support for the idea came from ice cores arduously drilled from the Greenland ice sheet. They showed large and disconcertingly abrupt temperature jumps in the past, on a scale not of centuries but decades.

The improved computer models also began to suggest how such jumps could happen, for example through a change in the circulation of ocean currents. Experts now predicted that global warming could bring not only rising sea levels but unprecedented droughts, storm floods, wildfires, and other weather disasters. A few politicians began to suspect there might be a public issue here. However, the modelers had to make many arbitrary assumptions about clouds and the like, and reputable scientists disputed the reliability of the results. Others pointed out how little was known about the way living ecosystems interact with climate and the atmosphere. They argued, for example, over how much CO2 humanity might be adding to the atmosphere through deforestation. One thing the scientists agreed on was the need for still larger and more coherent research programs. But the research remained disorganized, and funding grew only in irregular surges.

One unexpected discovery was that the levels of other "greenhouse gases" such as methane and chlorofluorocarbons were rising explosively. Suddenly scientists found that global warming could come twice as fast as expected — in their children's lifetimes or even their own. Gathering at a 1985 conference in Austria, climate experts from 29 nations agreed to call on the world's governments to consider forging international agreements to restrict greenhouse gas emissions. Policy makers ignored the advice, and the public scarcely noticed.

By the late 1970s global temperatures had begun to rise again as governments began to restrict smog and other pollution. Since the late 1950s some climate scientists had been predicting that an unprecedented global warming would become apparent around the year 2000. Their worries finally caught wide public attention in the summer of 1988, the hottest on record till then. Computer modeler James Hansen made headlines when he told a Congressional hearing and journalists that greenhouse warming was almost certainly underway. And a major international meeting of scientists in Toronto called on governments to undertake active steps to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

The response was vehement. Corporations and individuals who opposed all government regulation began to spend millions of dollars on lobbying, advertising, and "reports" that mimicked scientific publications, striving to convince the public that there was no problem at all. Environmental groups, less wealthy but more enthusiastic, helped politicize the issue with urgent cries of alarm. The many scientific uncertainties, and the sheer complexity of climate, made room for limitless debate over what actions, if any, governments should take.

In a field opened up by a handful of individuals who had taken a year or so off from their other work, now hundreds of scientists dedicated their careers, backed up by thousands of assistants and technicians. Some programs were huge, mobilizing cooperation among a dozen or more nations to provide data from weather stations, research ships, and (by far the most expensive) satellites to monitor temperatures, clouds, ocean currents, ice sheets and more. Their conclusions became increasingly reliable.

Was the global temperature rise due to an increase in the Sun's activity? That had seemed plausible to some, since for decades solar activity had been increasing in parallel with temperature. However, nobody could come up with a good explanation for how the slight changes in solar energy output could change climate so much. In the 1990s solar activity plunged while Earth's temperature climbed higher than ever, and most scientists concluded that solar activity could only be a minor influence. The issue was settled for good by a massive analysis of millions of measurements made in all the world's oceans. The observed long-term pattern of warming closely matched computer predictions of a greenhouse warming "signature," entirely different from changes that might be due to solar activity, volcanoes, or other possible influences on climate.

Some skeptics warned that the computer models were unreliable. If the models could reproduce the actual climate, that was only because the modelers had tweaked their parameters (for example, the numbers that described how clouds formed) until the models matched current climate data. Didn't that make them useless in calculating a different climate? But modelers gradually replaced their arbitrary tweaks with laboratory and observational numbers. And they began to match in detail not only the present climate but changes observed over the past century, and even the wholly different ice-age climate. Particularly convincing was a prediction that Hansen's team made shortly after a huge volcanic explosion polluted the stratosphere in 1991. They calculated a temporary global pattern of cooling over the next couple of years — and such a pattern in fact appeared.

The physics of clouds and pollution remained too complicated to work out completely. Modeling teams that fed different plausible assumptions into their computers got somewhat different results for particular regions, although always overall global warming. Rapid improvements in understanding of the many factors that affected the climate system did not reduce the uncertainties, for as new complexities were added they raised new questions. Into the 21st century, computer modelers continued to find roughly the same numbers as the Academy panel had found in 1979: if the CO2 level doubled, mean global temperature would rise 3°C, give or take a degree or two. If greenhouse gas emissions continued without restraint, warming would reach 3° before the end of the 21st century (and keep climbing beyond). It was a level that scientists now realized would be disastrous.

Meanwhile important news came from a French team's studies of ancient climates recorded in Antarctic ice cores, retrieved by a heroic Russian team from the coldest and most inaccessible place on Earth. They found that over hundreds of thousands of years, CO2 and temperature had been linked through feedbacks: anything that caused one of the pair to rise or fall brought a rise or fall in the other. As later evidence from other geological eras confirmed, a doubling of CO2 had always gone along with a 3°C temperature rise, give or take a degree or two — a striking confirmation of the computer model finding, by a wholly independent method.

At the end of the century a study of tree rings in ancient logs showed that during the century, global temperatures had abruptly soared to a level higher than anything in at least the past thousand years. Skeptics passionately criticized the "hockey-stick" shaped curve and even attacked the researchers themselves as frauds. But over the next decade, independent projects with other methods confirmed that temperatures had not only shot up, but faster and to a higher point than anything experienced since the emergence of our species. If the rise continued unchecked, large parts of the planet would become hotter than humans had evolved to survive.

In 1988 when scientists had first begun to call for restrictions on greenhouse gases, the world's governments created a panel to give advice on the issue. Although managed under the auspices of the United Nations, this Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was comprised of representatives appointed independently by each government. Hundreds, later thousands of experts donated their time to groups that convened to work out what could or could not be reliably said.

The IPCC was reluctant to make strong claims based mainly on computer models. It waited to see unimpeachable evidence that the global temperature was actually rising. Since the 1970s scientists had been predicting that the greenhouse warming "signal" would emerge from the noisy variability of weather around the turn of the century — and so it did. The oceans, for example, were heating up in exactly the pattern predicted by computer models of the greenhouse effect. In 2001 the IPCC managed to establish a consensus, phrased so cautiously that none of the government representatives ventured to dissent: a severe global warming was underway, and humans were the cause.

At that point the discovery of global warming was essentially completed. Scientists knew the most important things about how the climate could change during the 21st century, and what impacts might follow. How the climate would actually change now depended chiefly on what policies governments would enact.

In 1992 the world's leaders had met in Rio de Janeiro to discuss environmental problems. In a Framework Convention on Climate Change, signed by more than 150 nations, they solemnly promised to work toward preventing "dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system." The parties to the Convention agreed to meet periodically, and a 1997 Conference of the Parties in Kyoto set targets for industrialized nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But the developing nations refused to consider such reductions, and the U.S. Senate, spurred by a propaganda campaign funded by right-wing and industrial interests, rejected the Kyoto treaty in advance.

In the early 21st century the IPCC's conclusions were reviewed and endorsed by the national science academies of every major nation, along with virtually every other organization that could speak for a scientific consensus. Specialists meanwhile improved their understanding of some less probable but more severe possible impacts. For example, there were signs that disintegrating ice sheets could raise sea levels faster than the IPCC had suggested. Worse, new evidence suggested that the warming itself was causing changes in forests, tundra and wetlands that would release greenhouse gases to generate still more warming.

By 2010 impacts long predicted were turning up, sooner and worse than many had expected — acidification of the oceans, unprecedented deadly heat waves, record-breaking flooding and droughts, degradation of coral reefs and other important ecosystems. Some of the impacts had not been predicted at all, such as damage to health when smoke from monster wildfires spread across thousands of miles. An important new field of research developed as some scientists turned from calculating future impacts to showing how global warming was directly causing many billions of dollars in economic damage and killing many thousands of people right now.

Most obvious were changes in the Arctic, as predicted by scientists ever since Arrhenius — only faster. The Arctic ice pack was dwindling with unprecedented speed. Some experts warned that the melting of Greenland and parts of Antarctica were already irreversible: over centuries the seas would rise inexorably, perhaps too fast for coastal cities to adapt. Meanwhile it became clear that even if all emissions could be instantly halted, the gases lingering in the air would keep the planet warm for millennia.

Dozens of teams were now competing and cooperating in massive computer studies, which calculated that costly impacts would continue to climb as global temperatures rose. A 2018 IPCC report shocked the public by showing how the severity of damage would multiply if the global mean temperature got more than 1.5°C (2.7°F) above the pre-industrial level. Experts were appalled when the temperature touched that point already in 2023. Computer models, trained on past weather data, had difficulty calculating what was happening as the level of greenhouse gases continued to rise beyond anything seen in millions of years. However, over the past half century paleontologists had developed a suite of ingenious techniques to measure climates and gas levels in distant geological epochs. They reported that time and again, high gas levels had brought crises fatal to ecosystems, with "hothouse" climates far different from our own.

The scientists who had been predicting for decades that the world would get warmer were now obviously correct. Essentially all scientists along with most science journalists, business leaders, and much of the world public accepted the consensus. But in the U.S. (and to a lesser extent Canada, Australia, and Russia, nations with dominant fossil fuel industries), leading political figures and powerful media continued to scoff at the evidence. Studies had proved that to avoid catastrophic warming, a large fraction of the fossil fuel deposits that corporations and governments booked as assets must stay in the ground, yet they continued to open new oil and gas fields and even coal mines.

On the other hand, government subsidies for wind, solar power and electric cars were paying off, driving down the costs with remarkable speed. Western Europe began to reduce its fossil-fuel emissions, followed by the United States. World-wide, however, emissions continued to climb, with China and other developing nations taking the lead. The Kyoto agreement had failed. Taking a less ambitious approach, in the Paris Agreement of 2015 nearly all the world's governments volunteered individual targets for reducing emissions, and in later years they pledged further reductions. The new policies were not enough to avoid dangerous climate change, but they let scientists lower their estimates of future global temperature to a point where it seemed we might avoid a totally catastrophic heating.

If every nation met its target, what would they achieve? The science remained stubbornly imprecise, for the global climate system is a tangle of many interacting influences. Scientists did agree that without stronger and prolonged efforts we were most likely to get a rise approaching 3°C or more above the temperatures that had prevailed through human history. That would be a desperately wounded world, where it would be difficult to sustain a civilization that was widely prosperous and peaceful. And beyond what scientists found "most likely," we faced a distinct possibility of triggering unstoppable feedbacks that would heat the planet to a level where it would be difficult to sustain any civilization at all.

Diplomacy would have to press urgently for stronger pledges and see that they were fulfilled. The world’s climate experts explained that we had reached the point of crisis: we had delayed action for so long that we could now avoid grave harm only if global emissions did not just level off, but began to plunge by the year 2030. The policies set during the decade of the 2020s would determine the state of the planet’s climate for many thousands of years to come. Economic analysis showed that the expense of making the necessary changes in our economic and social systems would be far less than the cost of allowing climate change to continue, and would bring numerous other benefits. It was only necessary for people to fully accept the findings of climate science, which had proved over and over to be only too correct.

For remarks on the current situation and what we can do, see my Personal Note.

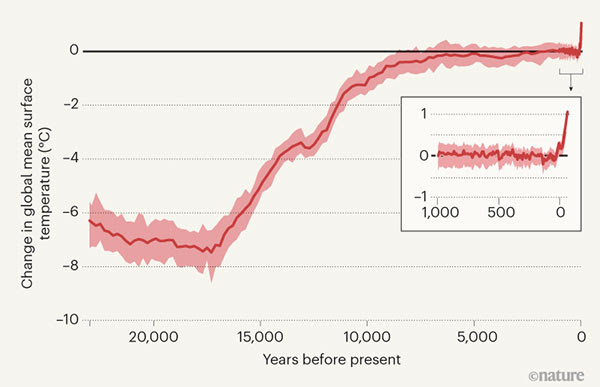

Global temperature over the past 24,000 years: a rise from the previous Ice Age, a period of unusual stability that fostered the rise of human civilization, and a sudden leap upward starting a century ago (inset) toward temperatures not seen in millions of years.

Marcott and Shakun (2021) with data from Osman et al. (2021). © Nature

Getting around: There are two sorts of essays here. Lengthy ones tell the history of some major development, such as computer modeling or international negotiations. Shorter ones delve more deeply into a particular topic — partly because it had an important impact, and partly to show some typical details of what was going on behind the scenes. At the end of most essays you will find links suggesting related supplementary essays (as enrichment) and major essays (as a path to continue through the main story).

In each essay, on the right of the text you will see links to essays about other topics. Follow forward an arrow to see how the events you are reading about gave something => TO the other topic. Follow back an arrow to track influence <= FROM the other topic (that is where you'll find the more complete account of a development). A double arrow <=> shows MUTUAL interaction.

Numbered notes like this: (12) give references. Notes with an asterisk, like this: (12*), have some informative text in addition. You can click on the note to go to its text and references, and once there you can click on a reference to reach the item in the bibliography. To return from the bibliography, use your browser's Back button.

To start in, the essay on Impacts of Climate Change shows why all this matters. For the scientific story, a good starting-point is the keystone essay on the basic discoveries about The Carbon Dioxide Greenhouse Effect, followed perhaps by attempts to explain changes with Simple Models of Climate. If you are interested especially in the social connections of climate studies you could start, for example, with the underlying facts of The Modern Temperature Trend and proceed to the long essay on U.S. Government: The View from Washington, followed by International Cooperation. For basic information and recent developments, see the page of links and bibliography.

Utilities: There is a Table of Contents (site map)... Milestones are listed in a timeline... Historians and climate scientists can find an introduction on methods and sources... References are listed in the bibliography. You can search this site.

The statements on this site represent the views of the author and are not endorsed by the American Institute of Physics. Two of the Institute's Member Societies have taken positions on climate change, see the American Physical Society's statement and the American Meteorological Society's statement, see also the American Geophysical Union's statement.

1. Schindler (1999). BACK

copyright © 2003-2025 Spencer Weart & American Institute of Physics