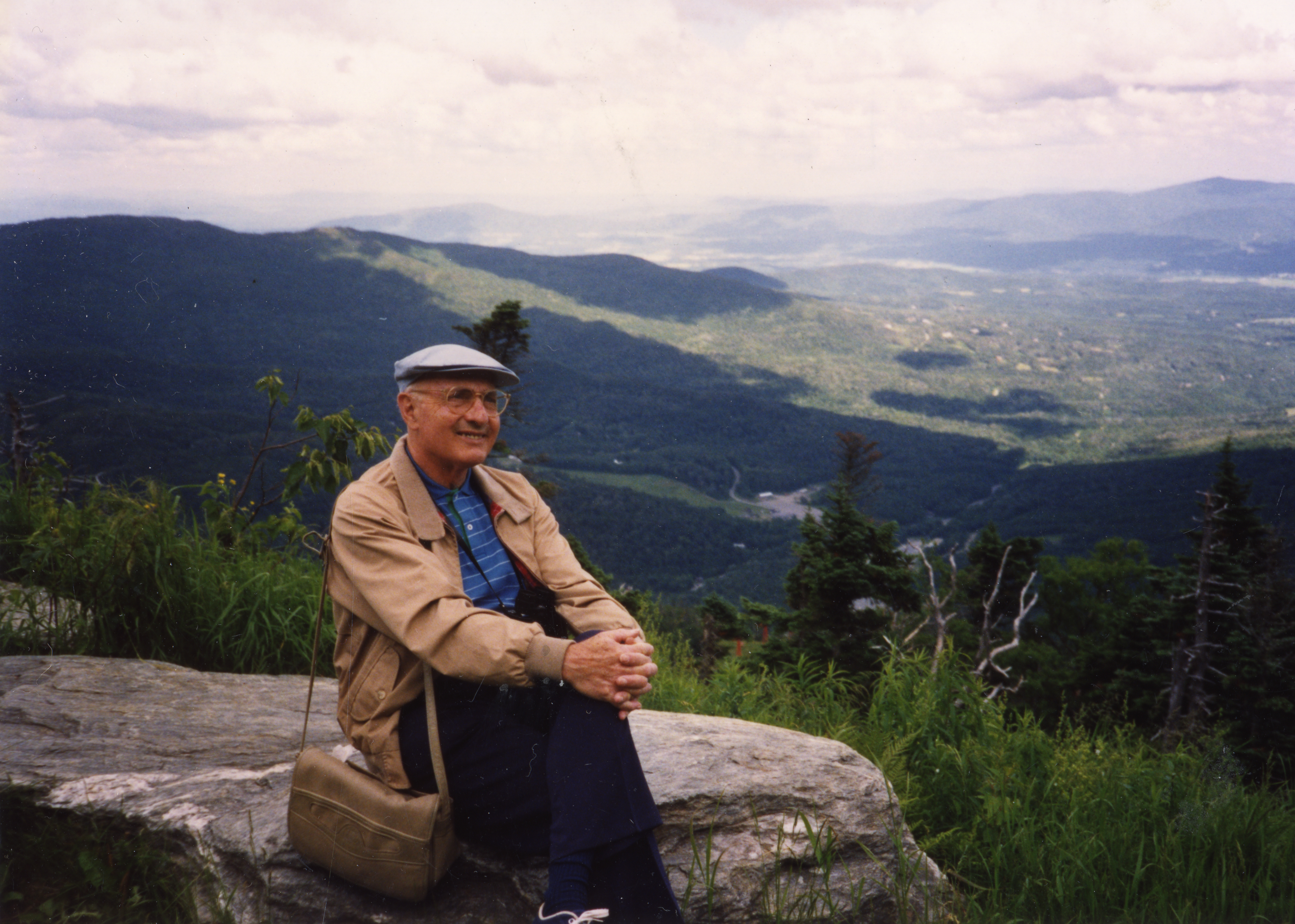

This exhibit describes the rise and fall of a large-scale research program on anthropogenic climate change. The program was organized and funded by the U.S. federal government in the late 1970s. The exhibit is based on the papers of William P. Elliott, an atmospheric scientist who was closely involved in the research effort. For more on climate history from the Center for History of Physics, visit The Discovery of Global Warming webpage, created by Spencer Weart.

The climate is changing, and through the combustion of fossil fuels, humans have been driving many of the changes that we experience today. The core scientific claim that humans can and have induced changes in the atmosphere that can be felt on the Earth's surface—a phenomenon known as anthropogenic climate change—has been settled for decades. In 1990, the first report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which is generally recognized as the authoritative scientific body on climate science, stated that anthropogenic factors were indeed changing the composition of the global atmosphere, causing the Earth’s surface to warm. Since then, the IPCC has worked to answer questions such as: how much warming will occur? How will different atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide influence global temperatures? What parts of our environment will be most affected by climate change? How will climate change shape global weather patterns? The core science is settled; experts now work to develop the edges of what we know. The possible futures for humanity, the environment, and the global climate have become clearer with every subsequent report.

While searching through the finding aids available on the Niels Bohr Library and Archives website, looking for possible episode material for an episode of Initial Conditions: A Physics History Podcast, I came across the William P. Elliott Papers on Carbon Dioxide and Climate Change, 1975-1996. Knowing a little about the history of climate science and understanding that the first meeting of the IPCC took place in 1988, I thought the Elliott papers seemed a bit early for scientific research on the topic of anthropogenic climate change. Asking myself what did scientists know about anthropogenic climate change in the 1970s, I began looking through the Elliott papers. I was able to reconstruct the history of the Carbon Dioxide Effects Research and Assessment (CDERA) program, a short-lived endeavor within the U.S. Department of Energy to research several topics pertaining to anthropogenic climate change. Despite only operating from 1978-1981, CDERA was a noteworthy undertaking. Perhaps most significantly, CDERA was a research program dedicated to the fairly narrow question of anthropogenic climate change that was funded and operated by the federal government. In its short lifespan, CDERA revealed the close relationship between climate science and climate politics in the United States. Specifically, it provides concrete examples of the divergent ways that the Carter and Regan administrations approached environmental and climate science. The whiplash that the sudden closure of CDERA in mid-1981 produced hit some scientists harder than others, but most noted that a promising young program had been cut down too quickly.

Finally, the memoranda, reports, letters, and journals contained in the Elliott papers give us a glimpse into how scientists themselves understood the changing climate in the 1970s. Some thought it was a dire issue, perhaps the largest problem humanity would face. Others acknowledged that climate change was an issue, but that more research was required before expecting the worst outcome. Still others, like Elliott, believed climate change was a threat but were pessimistic about the possibility of reducing reliance on fossil fuels. He believed that we would simply have to live with the effects of climate change. Perhaps the most striking aspect of the Elliott papers is how remarkably accurate, even at that early stage of research, CDERA's scientists were in predicting the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide fifty years later, in our present day. Taken together, the CDERA papers reveal the state of scientific knowledge about anthropogenic climate change in the late 1970s. They are, therefore, worth taking some time to explore. The language that scientists used nearly half a century ago is remarkably familiar, and in some instances, no less dire. We benefit, then, from learning about the cost of scientific and political inaction and reluctance to address anthropogenic climate change in the past, and perhaps we will reconsider making the same mistakes in the present

For the sake of simplicity, this exhibit uses the term “climate scientists” to refer to researchers in many different fields, such as meteorology, oceanography, physics, and atmospheric chemistry. They might have referred to themselves by their specific discipline, but since all were involved in climate research, the term “climate scientist” is the most succinct.