Rutherford's Nuclear Family

Mary Newton, 1896, a memento for Ernest to remember her while away from New Zealand. Credit: Rutherford Family, in Campbell, Rutherford, Scientist Supreme, plate B16.

Mary Newton, 1896, a memento for Ernest to remember her while away from New Zealand. Credit: Rutherford Family, in Campbell, Rutherford, Scientist Supreme, plate B16.

At each station in Rutherford's adult life — Cambridge, England as a post-graduate student, McGill University, Manchester, and back again to Cambridge — he surrounded himself with family and friends. Many of his colleagues passed through his homes or joined him on long holidays. Just as Rutherford pursued natural mysteries with vigor, he also enjoyed earthly communal life beyond the laboratory.

Even before Rutherford left New Zealand for England, aged 24, in 1895, he had settled the main question of his domestic life. While an undergraduate at Canterbury College in Christchurch he had rented a room from a local widow and become close to her eldest daughter, Mary Newton. Mary visited his family on holidays and they were unofficially engaged. She was his only romance. Later, as Lady Rutherford, she provided his continuous, domesticated thread. She was the core of Rutherford's nuclear family.

College Life in Cambridge

Ernest and Mary could not wed, however, until he could provide for a family, and so she remained in New Zealand when he journeyed to England. During his three years in the Cavendish Lab, young research student Rutherford wrote frequently to Mary. These letters tell of Rutherford's friendships and life beyond the lab. J.J. Thomson, he wrote, was "very pleasant in conversation and not fossilized at all."

Thomson immediately invited Rutherford to his house, where he met Mrs. Thomson and their sturdy 3-year-old son, George, who later received the Nobel Prize in physics himself. The Thomson household provided a model of collegiality that Rutherford later followed. Here he socialized with researchers passing through Cambridge and became friends with others, especially with the other “research student,” Irishman J.S.E. Townsend: “As he has no friends here he and I knock about together a good deal.” (Eve, pp. 15–16).

Townsend and Rutherford, as the first two research students from other universities to take a second degree at Cambridge, bonded as outsiders often do. On Thomson's advice, they both joined Trinity College, opening the door to sociability otherwise hard to find in the academic town.

Rutherford's letters to Mary in New Zealand reveal both his dedication to research and to getting ahead. He was driven and competitive, partly in hopes of advancing quickly to bring his wedding day nearer. He presented papers and submitted them to scientific societies and journals. He took only Sundays for relaxation. Rutherford wrote to Mary:

J.J. I believe openly declares that the new Research Students are a great success, and as I am at present the most prominent in that respect, I take a little of the praise unto myself. The more I boom of course the better it will be for me, for verily I must do something somehow, and verily the better it will be for thee since my fortunes are thy fortunes. (Rutherford to Mary Newton, 21 February 1896, in Eve, p. 27)

So Rutherford turned his experiments into entertainments. Rutherford's work on Hertzian or radio waves from 1895 to 1896 quickly built his reputation in Cambridge. He and Townsend and J.A. McClelland took his transmitter onto one of the town commons areas, an “expedition,” at a distance of 500 yards from his receiver. Although trying till 1 a.m., that expedition failed to detect a signal. Through the mediation of a Cambridge Don, Rutherford was offered use of the University Observatory for more trials. Rutherford succeeded in transmitting a signal from there back to town, a mile away. Science was proving to be both an entertainment and a spectacle. This, too, increased Rutherford's stature, leading to many invitations to lunch, tea, and dinner.

Rutherford came to love college life. When he returned to Cambridge in 1919 as Cavendish Professor, he typically enjoyed dining at Trinity College every Sunday evening. He took great pleasure in High Table and in the conviviality of conversation.

Family Life

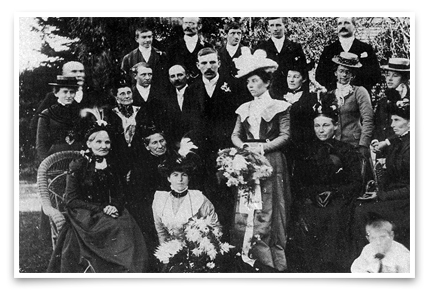

The wedding of Ernest and Mary Rutherford, 28 June 1900, in New Zealand. Ernest and Mary were back in Montreal in the northern autumn, in time for Ernest to teach again at McGill University. Credit: Rutherford Family, in Campbell, Rutherford, Scientist Supreme, plate B21.

The wedding of Ernest and Mary Rutherford, 28 June 1900, in New Zealand. Ernest and Mary were back in Montreal in the northern autumn, in time for Ernest to teach again at McGill University. Credit: Rutherford Family, in Campbell, Rutherford, Scientist Supreme, plate B21.

Ernest and Mary Rutherford married in New Zealand in 1900. Firmly established at McGill University, he could now support a family. He and Mary returned to Montreal via Hawaii and the Canadian Rockies in September, and on 30 March 1901 their only child was born. Rutherford crowed to his mother that Eileen Mary Rutherford had the usual number of limbs and healthy lungs, that Mary was pleased to have a daughter, and he hinted at his pride. The little family stayed in Montreal until Eileen was six years old, when Rutherford moved them all to Manchester, England.

Rutherford expected Mary to run the household and to free him to concentrate on his work, an arrangement common at the time. At this stage, his ambition often kept him at the university into the evening. As he wrote to a friend in July 1908, “I have now got through the stress of my first year and have got fat on it, at least my wife says so. At the same time I have never worked so hard in my life…”. (Eve, p. 180). That single-minded dedication paid off when Rutherford and Mary travelled to Stockholm in December 1908 and he received his Nobel Prize. Mary shared the honor and the rewards. As Rutherford wrote his mother, they had “the time of their lives” in Stockholm.

Their house, in a largely Jewish suburb of Manchester, was a two-mile tram ride from his lab at the university. The house was large enough that his friends Otto Hahn and Bertram Boltwood stayed with them during visits to Manchester. The Rutherfords also sometimes entertained his “research men,” as they did for Christmas dinner in 1909.

With the move to Cambridge in 1919, the Rutherford's bought a large “cottage,” a short walk across the River Cam from the Cavendish Lab. Eileen was then 18 years old. Two years later, Eileen married the mathematician Ralph Fowler, and together they provided two grandsons and two granddaughters to the Rutherfords. The 1920s provided the Rutherfords their most active family time. But Eileen died in 1930, aged 29, of a blood clot, a week after childbirth. Rutherford took badly the loss of his only child, but he found solace in his grandchildren for his remaining years.

Social Life in the Lab

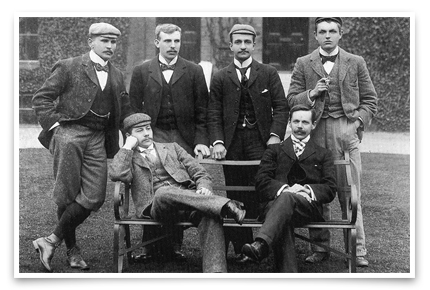

Over Easter holiday in 1896, Rutherford took a cycling holiday to Lowestoft, Sussex, with classmates. On the left is Richard Maclaurin, another New Zealander, and then Ernest. The others are not identified. Credit: Rutherford Family, in Campbell, Rutherford, Scientist Supreme, plate B17.

Over Easter holiday in 1896, Rutherford took a cycling holiday to Lowestoft, Sussex, with classmates. On the left is Richard Maclaurin, another New Zealander, and then Ernest. The others are not identified. Credit: Rutherford Family, in Campbell, Rutherford, Scientist Supreme, plate B17.

Rutherford promoted informal interaction in the lab wherever he presided. The record is strongest on this for his Manchester and Cavendish professorship periods. Edward Andrade worked under Rutherford at Manchester 1912–1914 and relates that the daily afternoon teas were a "great feature of the laboratory life." Rutherford sat at the table with all the rest for tea, biscuits, and conversation. They discussed science, of course, but also literature and "general gossip of the day." (Andrade, p. 124). The Australian Mark Oliphant, who worked in the Cavendish Lab from 1927 to 1937 and was Rutherford's last close collaborator, remembered these daily teas. Oliphant recalled that Lady Rutherford provided the tea, and sometimes even poured the tea, but that the buns (sticky) were supplied by the researchers. At Cambridge, tea was taken standing, so no one could linger long and avoid work (Oliphant, pp. 52–53).

Time in the Country

Rutherford's first adventure of note was a student holiday in 1896. He went to the Suffolk coast in the company of two “Afrikanders,” two other New Zealanders, and an Armenian, where they rented a cottage on the beach at Lowestoft for three weeks between terms. They rose early each day, went for a bracing swim “en règle,” alarmed local spinsters (as Rutherford wrote), and were guided by cooperative policemen to a place where nudity was rather out-of-sight. “Swimming was pretty cold of course, but one felt in pretty good trim after it.” He reported to Mary that they also bicycled, sailed, “loafed about the beach,” and: “Oh, how we did eat.” In the end, one man returned to Cambridge by train with the luggage, while Rutherford and the others cycled the 90 miles home in one day. (Eve, pp. 31–33) Rutherford loved a good stay in the country and always would.

Rutherford firmly believed in balance between the hard work of the school term and the outdoor life during holidays. In 1910 he bought his first motor car, a Wolseley-Siddeley, writing to his mother: “It is very desirable to have some means of getting fresh air rapidly.” In the spring holidays, they drove over 500 miles around England at speeds as high as 25 mph! “We can go 35 or 40 if we want to, but I am not keen on high speeds with motor traps along the road and a ten guinea fine if I am caught.” Even at these low speeds, the Rutherfords thought nothing of driving to Wales and back on a 3-day trip.

The automobile allowed the Rutherfords to holiday in Wales, where they took long walks and enjoyed the fresh air. In the 1930s, they decided to build a cottage closer to Cambridge and somewhere not so cold and wet. Lady Rutherford found a spot in the Wiltshire downs, with elm trees, a rookery, a pond, and a southern exposure. Chantry Cottage was erected, and for a few years, Rutherford spent holidays gardening, reading, and relaxing. He may have been at the center of the scientific world, but he remained a country boy at heart.

Golf

J.J. Thomson introduced Rutherford to golf in 1896. Never much for sport, this was at first strange to Rutherford. J.J. took him by train to Royston Heath, not far from Cambridge, and taught him the basics. As Rutherford wrote to Mary: “We knocked the ball about a bit and I learnt to knock the ball a considerable distance, if not very straight.” He confided that he did not think he was “quite old enough” to be an enthusiastic golfer (Eve, 34).

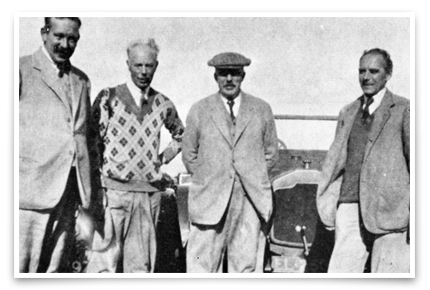

But Rutherford warmed to the game. His greatest time as a golfer was in the 1920s and 30s, in his 50s and 60s. He played many Sunday mornings at Gog Magog Golf Course on the southern edge of Cambridge with a group of Trinity College men. They called themselves the “Trinity Circus” or the “Trinity Menagerie.” Others called them the “Talking Foursome.” The group included at different times Frederick George Mann, Charles D. Ellis, Ralph Fowler, Francis Aston, Charles Galton Darwin, Geoffrey I. Taylor, and others. Lady Rutherford often went along for the walk and conversation.

Rutherford loved a good game of golf on Sundays with the “Talking Foursome” from Trinity College. Some sources say this is at Gog Magog Golf Club near Cambridge. Others place it in South Africa in 1929, during a British Association meeting. L–R: Ralph Fowler, F.W. Aston, Rutherford, G.I. Taylor. Credit: Eve, Rutherford, p. 340.

Rutherford loved a good game of golf on Sundays with the “Talking Foursome” from Trinity College. Some sources say this is at Gog Magog Golf Club near Cambridge. Others place it in South Africa in 1929, during a British Association meeting. L–R: Ralph Fowler, F.W. Aston, Rutherford, G.I. Taylor. Credit: Eve, Rutherford, p. 340.

Rutherford delighted in the camaraderie and open air of the golf course. Sometimes he focused on the game, but often the conversation took precedence. Rutherford reminisced, he talked shop, and he made irreverent jibes at chemists and at his colleagues. He sometimes relocated another player's ball into the rough just to get a reaction. Tempers could flare, but mostly the talk was jovial.

Rutherford and his friends played unusual varieties of golf, one called four-ball, in which four players each play a ball. The four players form two teams and the best ball wins the hole. In foursomes and sixsomes, two other games Rutherford enjoyed, each team played just one ball, with team members taking turns hitting the ball. Rutherford was not above gentle rebukes — and occasional peevishness — when his partners let him down.

Rutherford anticipated the end of term at the university, when he and his “Talking Foursome” might arrange a holiday around golf. Just after the annual Oxford-Cambridge Rugger Match (which Rutherford also enjoyed watching immensely), the crew drove to Brighton or Sussex for a few days on the course. The release golf provided from Rutherford's intense schedule during term was a constant counterpoint in his adult life. Rutherford golfed until the end. In early October 1937 he joined G.I. Taylor and F.G. Mann on the course, hittikng the ball about and discussing, of all things, organic chemists and their work. The next week, Lady Rutherford telephoned Mann to say Ernest was ill and could not play. A few days later Rutherford died.