Money for Keeling: Monitoring CO2 Levels

Money for climate change research was never easy to find. This essay focuses on a single example: support for monitoring the global level of carbon dioxide gas. Funds initially came from universities that sponsored research into unrelated agricultural, meteorological, and purely scientific questions, from corporations that developed instrumentation for industrial processes, and from military services that needed geophysical information and infrastructure for their Cold War operations. Only later did the U.S. government provide funds from programs that were partially concerned with global warming itself. These programs were disorganized, underfunded, and politically fragile, facing opposition from people who did not want to see evidence that industry was bringing harm. The most crucial support for the monitoring work was the energy of scientists. Without their tireless efforts to keep funds coming, the work would have faltered and left us dangerously ignorant. (For another case study of funding see the essay on Roger Revelle's Discovery.)

| Measurements of the level of carbon dioxide gas ( CO2) in the air would turn out to be of profound interest for the future of the world. But at the outset, nobody thought the problem was particularly important. Early studies of atmospheric CO2 were strictly a matter of satisfying general scientific curiosity, and their funding came from the usual sources for university research. Individuals would work on CO2 for a few months, supported on their salary as a professor, with perhaps a little help from a government grant awarded mainly for other matters. No wonder, then, that in the 1950s researchers lacked what they needed most, and what some were beginning to call for — reliable measurements of how much CO2 was in the atmosphere.(1) | - LINKS - |

| The problem was highlighted at a conference in Stockholm in 1954. The conference's goal was a practical one: to discuss how the atmosphere carried around gases that crops needed to grow, such as nitrogen and CO2. The participants agreed that there ought to be a network of stations to provide regular data on such gases. They thought priority should go to CO2, not least because it might alter the climate.(2) Heeding the call, educational institutions allocated some money and set up a network of 15 measuring stations throughout Scandinavia. Their measurements of CO2 fluctuated widely from place to place, and even from day to day, as different air masses passed through. A factory, a forest, a flock of sheep would change the level of the gas. That might be of interest to meteorologists and agriculture scientists, but it was useless for global warming studies. "It seems almost hopeless," one expert confessed, "to arrive at reliable estimates of the atmospheric carbon-dioxide reservoir and its secular changes by such measurements..."(3) | |

| Charles David (Dave) Keeling, a postdoctoral student at the California Institute of Technology, thought he could do better. Underlying his interest was a personal drive. Keeling was a dedicated outdoorsman, spending all the time he could spare traveling woodland rivers and glaciated mountains, and he chose research topics that would keep him in direct contact with wild nature. Monitoring CO2 in the open air would do just that. Keeling's case was not an unusual example of crucial "support" provided for geophysics from simple love of the true world itself. On lonely tundra or the restless sea, when scientists devoted their years to research topics that many of their peers thought of minor import, part of the reason might be that these particular scientists could not bear to spend all their lives indoors. Yet their research sometimes turned out to be more significant than even they had hoped. | |

| Keeling, like some of the Scandinavians, began studying CO2 in the atmosphere with a look at the gas's biological interactions, vaguely invoking possible applications to agriculture. But his research director, Samuel Epstein, found money for the work by relating it to a matter of even greater interest in the Los Angeles area: deadly smog. In 1954 Epstein applied to the Southern California Air Pollution Foundation, created the previous year by automotive and oil companies to study the smog problem, requesting funds for a survey of CO2 around California. | |

| Keeling's true scientific interest, however, was the pure study of geochemistry. As he explained in early 1956 while seeking funds from the U.S. Weather Bureau, he deeply desired to elucidate "the factors controlling the composition of atmospheric CO2." That basic question pointed toward measuring carbon isotopes such as carbon-14, and Harrison Brown, a senior Caltech geochemist, encouraged Keeling to pursue that. In the manner typical of postdoc students' mentors of the time, Brown helped Keeling get support from an Atomic Energy Commission contract (the AEC was naturally curious about isotopes in the atmosphere, in particular from its frequent atomic bomb tests). | |

| Keeling's research program and his exacting personal standards pushed him to make measurements at a level of accuracy that no instrument on the market could reach. He scoured the scientific literature for better ideas. Eventually he found a 1916 paper about a manometer (a device for measuring gas pressure) which he could adapt for his purposes, if only by putting in plenty of labor and ingenuity. His next problem was extracting CO2 from the air in precise quantities. The Scandinavians who had been measuring the gas used a simple chemical method, good enough considering how much variation there was in their samples. Keeling insisted on doing better. He learned that Harmon Craig, a young scientist in Chicago who was also measuring carbon isotopes, used liquid nitrogen to chill air samples and liquefyi the CO2 to extract it. Borrowing the idea, Keeling set out to measure carbon isotopes in the air at various locations around California. | |

| Keeling visited wilderness areas all around California, laboriously refining his techniques. He was surprised to find that at the most pristine locations he kept getting the same stable number — a true base level of atmospheric CO2. The Scandinavians who were monitoring the gas had scarcely imagined looking for such a thing.(4) | |

| Keeling recognized that the base level was significant, for he was interested in the greenhouse theory of climate change. His mentor Harrison Brown had recently published a book that introduced many people to a shocking new idea: the explosive, exponential growth of population and industry over the coming century would exploit resources on a planetary scale.Keeling and his research supervisors were also familiar with theoretical studies that Gilbert Plass had underway (published in 1956) which made the CO2 greenhouse effect sound plausible. Plass was working nearby in the Los Angeles area and came up to CalTech to discuss the topic |

More discussion in |

| Already in his 1954 application to the Air Pollution Foundation, Epstein had mentioned that recent studies of century-old tree rings indicated that burning fossil fuels was adding CO2 massively to the atmosphere. He remarked that. "a changing concentration of the CO2 in the atmosphere with reference to climate" may "ultimately prove of considerable significance to civilization." It is doubtful that this made any difference in the foundation's decision to fund Keeling's modest survey. The greenhouse effect was an obscure speculative topic of no practical significance for the present century, if ever. Nor was it likely to yield new information without great effort. This was not research any foundation or agency had good reason to support.(5) | |

| Just at this time, however, planning was underway for an International Geophysical Year. Scientists and governments organized the IGY in response to a combination of altruistic and Cold War motives, ranging from a hope to promote international cooperation to a quest for geophysical data of military value. The project would extract a large if temporary lump of new money from the world's governments. Greenhouse gases like CO2 were too low on the list of IGY concerns to be allocated much support, but with so much money now available, a little might be spared. | <=International |

| A modest plan crystallized in meetings of experts arranged by the U.S. National Committee for the IGY in early 1956. Here two senior scientists, Roger Revelle and Hans Suess, argued the value of measuring CO2 in the ocean and air simultaneously at various points around the globe. The ultimate goal was "a clearer understanding of the probable climatic effects of the predicted great industrial production of carbon-dioxide over the next 50 years." But the immediate aim was to observe how seawater took up the gas, as just one of the many puzzles of geochemistry. Revelle had become interested in the question through his own research, which had been amply supported by the U.S. Navy's Office of Naval Research and other federal agencies, whose interest in the oceans was whetted by the competition with the Soviet Union. |

|

| The committee granted Revelle some small funds for measuring CO2. The key actor in this, and much else in getting greenhouse gas studies underway, was Harry Wexler, a meteorologist turned administrator who served as Chief of the Scientific Services division of the U.S. Weather Bureau. Wexler was an outstanding example of the thoughtful officials who worked behind the scenes to identify and promote promising research, while the scientists they supported got all the credit.(6) | |

| Wexler and Revelle already had Keeling in mind for this work, and Revelle now hired the young geochemist to come to the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and conduct the world survey. One of their aims, as Keeling recalled it, would be to "establish a reliable 'baseline' CO2 level which could be checked 10 or 20 years later." To actually detect a rise of the CO2 level during the 18-month term of the IGY scarcely seemed possible.(7) Obedient to his sources of funding, Keeling scrupulously measured CO2 variations in the sea and air at various locations. But his heart went into something more fundamental, the atmospheric "baseline" value. | |

| Keeling wanted to buy a new type of gas detector (namely, infrared spectrophotometers) that penned a precise and continuous record on a strip chart. Development of these instruments had begun in academia, and in the late 1930s little entrepreneurial firms took up the technology. The firms received a big boost from government orders during the Second World War, but afterward they also developed instruments for monitoring civilian industrial processes. It was wholly fortuitous that they could accurately monitor CO2 not just in a factory but in the atmosphere at large. Most of Keeling's seniors thought that such instruments were more costly than anyone needed to measure something that fluctuated so widely as atmospheric CO2 levels. Yet the IGY money pot was big enough, and Keeling persuasive enough, to get Wexler to dig up funds to buy the spectrophotometers.(8) | |

| The survey's logistics, like its instruments, depended on things that happened to be available for unrelated purposes. One linchpin would be a weather observatory built in 1956 atop the volcanic peak Mauna Loa in Hawaii. Rising above the lower atmosphere and surrounded by thousands of miles of clean ocean, it was one of the best sites on Earth to measure undisturbed air. Funding for the Mauna Loa Observatory was split between the U.S. Weather Bureau and the National Bureau of Standards. It was also reported that "The Armed Forces are keenly interested in some of the projects at Mauna Loa" thanks to concerns with high-altitude equipment and monitoring satellites.(9) The military accordingly provided help for road-building and the like. | |

| Another key station would be in the pristine Antarctic, where scientific work depended wholly on military assistance. It was almost a parable, the coldest of Cold War science. The U.S. Navy and other services, intent on developing expertise that would prepare them for warfare under any circumstances, would gladly pick up some credit along the way by giving scientists heroic logistical support. This was only one of many ways that the Navy and other armed services, by funding work connected with their military missions, provided essential support for research that would turn out to tell something about climate change. | |

| When Keeling set up his recording spectrophotometers at these stations, they proved to be worth their cost. Spikes in the record on the strip charts pointed to CO2 contamination blowing past from volcanic vents on Mauna Loa, and from machinery in Antarctica. Stalking such problems with a meticulous attention to detail that verged on the obsessive, Keeling managed to extract a remarkably accurate and consistent baseline number for the level of CO2 in the atmosphere. In late 1958, his first full year of Antarctic data hinted that a rise had actually been detected. |

|

| But the IGY was now winding down, and by November 1958 the remaining funds had fallen so low that CO2 monitoring would have to stop. Suess came to the rescue. "I am sure that this [monitoring] program should be continued under all circumstances," he wrote to Revelle. He asked Revelle to transfer some ten thousand dollars of IGY money, earmarked for Suess's studies of carbon-14, to support Keeling's program. (In those years, more than now, agencies trusted scientists to spend funds as they chose.) To fund his own laboratory, Suess would turn to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, always willing to support work with radioactive isotopes.(10) The incident shows that it is sometimes beside the point to identify the exact source of funds for a given year of work. What mattered was the generally flexible and resource-rich environment for geophysics, an environment that could sustain a relatively small and marginal project like Keeling's if senior scientists thought it worthwhile. | |

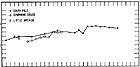

| Meanwhile Keeling applied to the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF). The NSF's budget was on the rise, not least because Americans were concerned about the launching of the Sputnik satellite and other signs of Soviet scientific prowess. Keeling eventually got funds to carry on longer.(11) In 1960, with two full years of Antarctic data in hand, he published an epochal finding. The baseline CO2 level in the atmosphere had detectably risen, and at approximately the rate Revelle calculated for oceans that were not swallowing up all of human industry’s emissions.(12) As the Mauna Loa data accumulated, the record grew increasingly impressive. The CO2 levels climbed noticeably higher, year after year. |

|

| But just when the data were beginning to look solid, the U.S. Congress pruned back the federal budget, science agencies included. The Weather Bureau had to stop funding research not directly related to forecasting. Keeling had to abandon the expensive and time-consuming Antarctic monitoring. The Mauna Loa Observatory meanwhile suffered deep funding cuts — at one point the staff were told the station would probably be closed altogether. That would mean terminating the CO2 monitoring program, which needed roughly $100,000 a year to function. It was only by strenuous efforts that Keeling and his allies managed to scrape up enough money from the NSF to continue gathering the indispensable data. Meanwhile in Spring 1964 the delicate instrument broke down despite long hours of work by staff on the mountain, a misfortune that Keeling used in arguing for more money so he could hire a full-time technician. The hiatus is visible for all time to come in Keeling's graph of the history of the Earth's CO2.(13) |

|

| Keeling afterwards reflected on what might have happened if his funding had been cut off before he nailed down his results. The Scandinavian scientists did eventually work out the flaws in their techniques, but they were inevitably plagued by random variations at their sites, swept by winds from farmland and ocean. Keeling rightly pointed out, "Many years might have passed before data of the quality of the Mauna Loa record would have been forthcoming."(14) |

|

| What had begun as a temporary job for Keeling was turning into a lifetime career — the first of many careers that scientists would eventually dedicate to climate change. The 1963 funding hiatus was not the last of his problems. To sustain the Mauna Loa observations over the next two decades, he and his supporters had to keep up what one administrator called "a nontrivial fight."(15) Atmospheric studies were divided among many Federal agencies, which made for bureaucratic problems as officials argued over which of them, if any, should take charge of which aspects of CO2 research. Scientists mostly had to seek support from either the NSF or the Weather Bureau (which was later incorporated into a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA). | |

| In 1965 a panel appointed by the President's Science Advisory Committee gave high-level endorsement for monitoring CO2 levels "for at least the next several decades." The endorsement only ensured a bare minimum of funds for the next few years, however.(16) By 1970, severe cuts again threatened the program. | |

| This weak position was further weakened, as so often in human affairs, by personality issues. Some officials would have preferred to pursue CO2 monitoring without Keeling himself. "Keeling's a peculiar guy," Revelle later remarked. "He wants to measure CO2 in his belly... And he wants to measure it with the greatest precision and the greatest accuracy he possibly can." As he stubbornly sought more money to improve his results and complained angrily about shortfalls, Keeling struck some people as a demanding "know-it-all." But when it came to monitoring CO2, Keeling really did know it all better than anyone else. There was nobody so reliably skilled nor so dedicated. Although a few other scientists in the United States and around the world also undertook studies of CO2 levels, in the end Keeling and his staff at Scripps kept control of the core of the monitoring work.(17) | |

| Besides putting up with Keeling's exacting requirements, agencies had to deal with a kind of science they found unattractive. "Monitoring" a gas in the atmosphere seemed just dull plodding around a beaten track, calling to mind the discredited statistical climatology of an earlier generation. The NSF was supposed to fund pathbreaking science, and officials looked for striking new results, new ideas that could be published in leading scientific journals — not just that steady, relentless upward march of data points, year after year after year. A reviewer who grudgingly supported one of Keeling's proposals remarked in 1979, " CO2 monitoring is like motherhood.... It does appear, however, that the former is even more expensive." Keeling did produce some interesting findings by studying variations in the rate of rise of the gas, from its seasonal cycle to decade-scale accelerations and slowdowns. But renewing his support was always a struggle. Officials at NSF told him bluntly that they would not support "routine monitoring" indefinitely. At one point he was asked to draw a line separating the "basic research" component of his work from the "routine monitoring" part, so that the latter could be foisted off on some other agency. Keeling did not reply to the request.(18) | <=Climatologists |

| The straightforward solution would have been to fund CO2 monitoring as just one piece of a grand program to monitor all aspects of the global environment. Here the story of support for greenhouse effect studies becomes part of the general tale of government funding for environmental matters. The grassroots environmental movement that came to maturity around 1970 made concern for the environment a major government responsibility, watched closely by the public. Influential reports by panels of scientists demanded more research and, in particular, more monitoring of how human actions affected the environment. Bureaucrats put carbon dioxide into a new category, "Global Monitoring of Climatic Change." Under this title the funding, stagnant for many years, doubled and doubled again between 1971 and 1975.(19) |

|

| The Mauna Loa Observatory, again threatened by funding cuts, was rescued when a unit of NOAA took over its operation and maintenance in 1973. This unit was the Air Resources Laboratories within NOAA's Environmental Research Laboratories— names that reflected the new national concern about the environment. Formally, the money came out of a budget for "inadvertent climate modification," and fell within the agency's general responsibility for monitoring "air quality." The administrative structure for the monitoring was directly descended from an organization that the Weather Bureau had created in 1948 to help the Atomic Energy Commission track the dispersion of radioactive fallout from atomic bomb tests. This responsibility was later expanded to include tracking of urban smog and other materials artificially added to the atmosphere. CO2 was stuck into this budget for lack of any better place to put it.(20) Meanwhile, NSF continued to periodically award Keeling grants for specific research projects at Scripps. | <=Government |

| Further support came from officials and scientists who began to call for international funding and organization of environmental monitoring. In his battle for U.S. government funds, Keeling rounded up verbal endorsement from the World Meteorological Organization (a prestigious intergovernmental body that monitored global weather), and he got some money directly from the new United Nations Environmental Programme.(21) But hopes that other nations would join the effort with their own monitoring efforts were disappointed, and NOAA's program was the only truly global one. Unfailingly meticulous, Keeling was trusted to set standards for the tricky measurements of air samples, brought to him in glass flasks from spots around the world. These measurements confirmed the Mauna Loa results for the inexorable annual rise of CO2, and added important information about the seasonal carbon cycle. |

|

| In a 1976 summary publication that unequivocally demonstrated the long-term rise of atmospheric CO2, Keeling's group ended, as was customary in scientific papers, with an acknowledgment of support. They cited a series of six NSF grants, and added that NOAA and its predecessors had provided "station facilities, field transport, and staff assistance." The scientists might also have noted, had they not taken it for granted, that their institutional homes provided an essential long-term foundation of salaries and facilities. Nearly all senior scientists get their pay, their office, and (sometimes hardest to secure) their parking space, in their capacity as a university professor, or sometimes as a staff member of a public or private research institute. Keeling's group, in the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, got its basic money not only from Federal government grants but also from the State of California and through private institutional fund-raising and endowments.(22) | |

| The NOAA monitoring program's budget leveled off after 1975, as part of a general saturation of environmental concern. But now a new actor came on stage. In the mid 1970s David Slade, a vigorous and strong-minded manager in the Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA), took an interest in climate change. More than almost any other manager, he saw the greenhouse effect as a matter of serious concern to the energy industries. It was part of the new agency's mandate to take a hard look at energy and the environment in general. Meanwhile some scientists were warning officials that climate change was emerging as a serious issue. The geochemist Wallace Broecker, for one, wrote to ERDA's chief in 1976 to insist that the agency "make every possible attempt to explore the effects of CO2."(23) | |

| With such backing, Slade sought the authority and budget to support a variety of research programs, including better CO2 monitoring. His first move was the creation in 1977 of a prestigious Study Group on the Global Effects of Carbon Dioxide, chaired by the veteran nuclear energy administrator Alvin Weinberg. As an advocate of nuclear power — the leading alternative to energy production from fossil fuels — Weinberg became a strong supporter of greenhouse effect studies. Next, Slade set up an Office of Carbon Dioxide Research, a vessel into which he hoped to pour important sums of money.(24) He mobilized scientists around the country to help draft an elaborate research program. The plans called for increasing the annual budget for greenhouse effect research more than tenfold, to $20 or $30 million, including a global CO2 monitoring network costing around $200,000 per year.(25) | |

| As these discussions proceeded, ERDA was integrated into the newly created Department of Energy (DOE). That only increased the uncertainty among government officials about who should pay for Keeling's and other CO2 monitoring. Work was being funded by DOE, NSF, NOAA, and even the U.S. Geological Survey. Of them all, only Slade at DOE seemed interested in taking responsibility as the "lead" Federal agency for CO2 monitoring with an aggressive program. From 1977 to 1980 his small budget doubled, redoubled, and redoubled again, driving an expansion of many kinds of research related to CO2 and global warming. However, not all of this represented a net increase of total Federal funding for climate research. Much of the money was only shifted about in administrative rearrangements. Keeling's work continued to be funded precariously by grudging contributions from several agencies. | |

| Slade's operation was the closest the nation had ever come to a centrally organized program to study climate change, but DOE was a poor place for such work. Those who dealt with any branch of the new department (including me, the author of these essays) were often frustrated by its bureaucratic quagmire of paperwork and regulations. Pushing a research program like Slade's meant an interminable succession of meetings with scientists, other Federal science agencies, the Office of Management and Budget, a variety of advisory and oversight committees, and foreign groups. Along with this came endless writing, revising, and re-writing of plans and reports. As one of Slade's staff members complained, "Nobody gets to do any work except bureaucrats and secretaries." Sometimes it seemed that more time was spent on convening workshops to discuss research than on the research itself. "If anything has been meetinged to death it's CO2," the staffer remarked. "If conferences could solve problems, it should be solved by now."(26) Scientists began to worry. Particularly outspoken was Broecker, who wrote to a Senator that "the time for one complete loop (scientists to agency to scientists) is much too long... This system has functioned but it has led to delays and I'm sure has left huge gaps in the research program."(27) |

|

| Reinforcing this criticism of the DOE bureaucracy was the fact that the new department had no track record of work specifically on climate change, nor any special expertise in the field. And Slade's aggressive bureaucratic maneuvers made him unpopular with some administrators in other agencies. His ambitious plans ran into a wall. Congress was again fighting particularly hard to balance the Federal budget, and Slade's program had gotten big enough to attract the attention of frugal administrators. In 1980, the increases in his CO2 funding came to a halt. Meanwhile the Congressional National Climate Act of 1978 had established a National Climate Program Office — with the responsibility assigned not to DOE but to NOAA. The agency immediately expanded its program of collecting air in flasks by adding ten stations scattered around the world. Its global CO2 monitoring program has continued to this day.(28) | <=Government |

| The assignment of responsibility to NOAA was a problem for Keeling. The weather bureaucrats had grown weary of his demands and were getting ready to push him aside so they could monitor CO2 as they saw fit. Meanwhile NSF officials had decided to terminate their support of Keeling's "routine" measurements. At the start of 1981 it seemed that he had run out of sponsors. But Scripps's director made a personal appeal to Slade's boss, DOE Director of Energy Research Edward Frieman, who agreed to pick up the ball. Slade and his colleagues in DOE undertook some horse-trading with NOAA, and the Mauna Loa monitoring, including exacting standard-setting, continued under Keeling's control.(29) | |

| The reprieve was short-lived. In 1981, Ronald Reagan became President, eager to suppress "alarmist" environmentalism. Reagan's Secretary of Energy (a former governor of South Carolina, trained as a dentist) told people that there was no real global warming problem at all. The DOE's recent attempt to take over and expand greenhouse effect studies, smacking of bureaucratic empire-building, made a juicy target for cuts. To the dismay of the Department's own mid-level scientist-administrators, its new leadership announced plans to s abruptly cut funding for climate research. In particular, they would entirely terminate DOE's funding of CO2 monitoring. Slade, undercut by criticism of his administrative methods, was peremptorily removed from his post (Frieman too was forced out). | |

| Supporters of climate research rallied, finding a leader in Representative Albert Gore, Jr. Supported by a few other representatives, Gore held a Congressional hearing in March 1981 that featured testimony by persuasive scientists like Revelle and Stephen Schneider. The hearings threw a public spotlight on the threat to the CO2 program. Painfully embarrassed by media attention to greenhouse warming, which continued sporadically through the year, the Reagan administration backed off a bit, and the DOE program to monitor CO2 survived. (The other components of Slade's pioneering program of research on greenhouse warming, however, were dead for good.).(30*) |

|

| The CO2 budget was so small, and now so little appreciated, that DOE managers tried to persuade NOAA to take over Keeling's work. But under Reagan, environmental research was being starved at NOAA too, as at every Federal agency. The result of months of negotiation was a compromise, in which NOAA took on administration of some activities while DOE continued to provide money. Backed up by DOE (as well as by the World Meteorological Organization), Keeling was also able to return to NSF for funds from time to time. And he found other occasional but important sources. For example, in 1982 his research team got an unexpected grant from the Electrical Power Research Institute, a private group underwritten by the electrical power industry, whose leaders recognized that they needed a better understanding of the greenhouse effect.(31) For Scripps's day-in, day-out global CO2 monitoring, however, DOE remained the chief support. |

|

| Concern about global warming was spreading, and finally in 1989 the World Meteorological Organization established an international Global Atmosphere Watch that supplemented the NOAA network’s monitoring of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. Yet scientists continue to notice that, as one of them put it in general terms, "Monitoring does not win glittering prizes. Publication is difficult, infrequent and unread." Even as funding poured into ambitious new projects, some important series of routine measurements were interrupted when funding from one source or another halted. The CO2 curve, now world-famous as the "Keeling Curve," was one series that survived, mounting a step higher year by year. As Keeling's son Ralph (a leading geochemist in his own right) explained in 2008, "The Scripps program continues to be funded — if precariously — one grant at a time.... a hiatus may be only one political wind shift or economic downturn away."(32) |

|

| Indeed long after the importance of the Keeling Curve was universally acknowledged, in 2013 under President George W. Bush the work at Scripps was yet again almost killed by budget cuts. Dave Keeling had died in 2005; Ralph Keeling now directed the measurements. Appealing to the public, he launched a Twitter crowdfunder that raised enough money to pay salaries until the publicity brought in additional funding.(33) | |

| All the bureaucratic effort, which drained countless hours and emotional energy from administrators, politicians, and most of all from the Keelings and other scientists, was over an annual sum of barely $200,000, an insignificant fraction of DOE's multi-billion-dollar research budget. | |

A Lesson on General Trends in Science Funding in the United States in the second half of the twentieth century can be found in this story. The chief theme that historians have noticed in general, and which also appears in this story, is the impact of the Cold War. The fact that something like half of the research on anything in this period depended on military or national prestige concerns is so familiar by now to science historians, that one needs to note that roughly half of the support did not come from such sources. Other practical matters such as agriculture and air pollution, as well as pure academic curiosity, also figure in Keeling’s story and many others. |

|

| The trend most obvious and familiar to scientists who lived through the period was a shift from personal to bureaucratic funding mechanisms. In the 1950s, the geophysics community was small enough so that everyone knew each others’ qualifications, and leaders could make decisions on a personal basis (physicists, astronomers and most other scientists worked similarly). Officers of agencies like the U.S. Committee of the IGY or the Office of Naval Research could bestow funds like Renaissance Princes upon those they trusted. It was such patronage mechanisms that Revelle and Seuss used to deliver IGY money to Keeling, that Keeling himself drew upon to extract additional funds to buy his spectrometer, and that left Seuss and Revelle with no qualms about diverting money from a grant intended for a different purpose. | |

| This personal model became less prevalent through the 1960s, and by the 1980s it was all but extinct outside a few sheltered places like the Defense Department's Advanced Research Projects Agency. The shift of government research support to the NSF and other large new agencies made for more rigorous supervision, whether through formal peer review and committee mechanisms or, as in the DOE, by rule-bound bureaucrats. But the underlying reason for the shift was probably the sheer growth of research communities. Ever larger populations meant that a few leaders like Revelle could no longer know and judge everyone. Moreover, the funding required for a research program increased even faster than the number of researchers, since each step forward in knowledge meant that the next step would require more elaborate instrumentation and collaboration. Keeling's advanced spectrometer, and the coordination required to gather CO2 flasks around the world, were more costly than their predecessors, yet they were tiny next to the grand programs projected in other areas of meteorology and oceanography, to say nothing of space astronomy or high-energy physics. The large sums called up increased Congressional insistence on tight oversight and controls. | |

| The United States was not alone in these trends, but the trends were more pronounced there. In most other countries the central government bureaucracy, as the employer of the majority of academics, had already before 1940 played a main role in supporting research. And in the postwar era, the funding of research nowhere grew to such gargantuan bulk as in America. | |

| The spread of formal oversight structures was a problem for Keeling because his work did not fit easily into any of the slots. This feature was probably most common in the scientific fields (increasingly prevalent) that involved interdisciplinary work. Geophysics, inherently interdisciplinary, was liable to include research programs that fell between two chairs, subject to agency infighting over who would be privileged, or obliged, to pay for a given program. | |

| Mingled with this infighting came another trend: the politicization of some scientific decisions. Through the 1960s, science advice flowed upward from the research community to politicians and the White House (some would say "downward"). The direction began to reverse when President Richard Nixon grew disgusted with physicists' opposition to ballistic missile defense and other Cold War initiatives. Under the early Reagan administration, top officials not only rejected unwelcome advice, but actively sought to suppress research that might lead to further unwelcome advice. The tendency was at first most obvious in environmental areas like global warming and pollution control, but in time it spread into sexual education and other areas of public health, and onward to basic research involving embryos. |

<=>Government |

| Such politicization crept in more slowly and less extensively in most other democracies. The problems are probably connected to the unequaled rise to power in America of right-wing anti-intellectual, anti-elite attitudes. While increased bureaucratization of research support may be inevitable, interference for short-sighted political ends is an error that all citizens should oppose. | |

RELATED:

Home

Government: The View from Washington

The Carbon Dioxide Greenhouse Effect

Roger Revelle's Discovery

| NOTES |

1. Much of the following is taken from Weart (1997), q.v. for some additional references. See also Sundquist and Keeling (2009). For a general discussion of the Keeling Curve and its political setting see Howe (2014). BACK

3. Fonselius et al. (1955); Fonselius et al. (1956); a main problem was inadequate instrumental technique, see From and Keeling (1986), p. 88; "hopeless": Rossby (1959), p. 15, calling for more global measurements "during a great number of years.". BACK

4. "Factors" (underlined in the original): Keeling to Harry Wexler, 16 Feb. 1956, office files of C.D. Keeling. I am grateful to Keeling for access to these files, which have since been transferred to the SIO archives. Here and below see also Keeling (1958); Broecker and Kunzig (2008), pp. 73-78; Weiner (1990), pp. 15-25; Christianson (1999), pp. 152-54, and Keeling, interview by Weart, January 1995. BACK

5. Brown (1954); see also Putnam (1953), p. 170. Tree ring studies: see essay on "Roger Revelle's Discovery". Rebecca John, "New Evidence Reveals Fossil Fuel Industry Sponsored Climate Science in 1954," DeSmog.com (Jan. 30, 2024), online here. BACK

6. "Clearer understanding:" Minutes of IGY Working Group on Oceanography, Regional Meeting, 2 March 1956, Washington, DC, copy in provisional box 96, folder 243, "IGY-CSAGI Working Group on Oceanography," Maurice Ewing Collection, Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin. Wexler: see Fleming (2016). BACK

7. Keeling (1978), quote p. 40; similarly, Keeling, interview by Weart. For all this, see also Keeling (1998). BACK

8. Scripps Institution of Oceanography. "Proposal to the National Science Foundation for A Study of the Abundance of CO2...," prepared by Norris W. Rakestraw and Charles D. Keeling, ca. June 1958. Folder "Government Correspondence - NSF - 1958-1969," Keeling office files, SIO. See Keeling (1978), p. 38. BACK

9. New York Times, June 24, 1956. BACK

10. Funding crisis: Hans Suess to Roger Revelle, 14 November 1958, box 20, folder 24, Hans Suess Papers mss. 199, Mandeville Dept. of Special Collections, Geisel Library, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA Suess Papers. See also Suess to Harmon Craig, 11 November 1958, box 6, folder 13, Suess Papers. BACK

11. Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Proposal LJ-723 to National Science Foundation, 2 June 1958. Prepared by Norris W. Rakestraw and Charles D. Keeling. Folder "Grant - NSF G6542 Proposal," Keeling office files, SIO. See also Keeling (1998). BACK

13. Keeling, interview by Weart, January 1995, Keeling (1978); Keeling (1998), p. 46. For information on the breakdown of the infrared analyzer I am grateful to a personal communication from Forrest M. Mims III. BACK

14. Keeling (1978), p. 52. BACK

15. Quote: Berrien Moore III, personal communication, Sept. 1989. Here and below also Keeling, interviews by Weart, confidential communications from others, and papers in various files at NOAA Air Resources Laboratory, Silver Spring, MD. BACK

16. President's Science Advisory Committee (1965), p. 26. The panel recommended funding through "the U.S. Weather Bureau and its collaborators," p. 127. BACK

17. Roger Revelle, interview by Earl Droessler, Feb. 1989, AIP. For the program and methods around this time see Keeling (1970). BACK

18. Anonymous review, Oct. 1979, Folder "Grant - NSF ATM79-25965 Proposal," Keeling office files; Keeling (1998), pp. 51-52, 56-57. Asked to draw a line (sometime in the 1970s): Ralph Keeling (2008), p. 1771. BACK

19. Hart (1992), p. 32-33, citing U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Appropriations, "Appropriations for State, Justice, Commerce" for FY 1967-1975. BACK

20. L. Machta, "A History of the Air Resources Laboratory," draft, Feb.1990. BACK

21. Keeling (1998), pp. 51-52. BACK

22. Keeling et al. (1976), p. 551. In such papers institutions are acknowledged at the outset by listing authors' affiliations. BACK

23. Broecker to Robert Seamans, 17 March 1976, copy in Revelle Papers MC6 19:32, SIO. BACK

24. D.H. Slade, "Plan for the DOE Carbon Dioxide Effects Program," 14 Oct. 1977, Wm. Mitchell Papers, NOAA Air Resources Laboratory, Silver Springs, MD. See Science News (1977). BACK

25. Various plans in Revelle Papers MC6 12:15, SIO. BACK

26. Elliott (1977-89), 13 Nov. 1978 and 21 Aug. 1980. BACK

27. Broecker to Sen. Paul Tsongas, 7 April 1980, "CO2 history" file, office files of Wallace Broecker, LDEO. BACK

28. A list of stations with dates is at this NOAA site. BACK

29. Keeling (1998), pp. 56-61; Fleagle (1994), p. 126. BACK

30. Main supporters were Reps. George Brown (CA), a long-time friend of science, and James Scheuer (NY). Schneider (1989), pp. 121-130; Jensen (1990). For the ERDA/DOE climate program and its termination see Justin Shapiro, "Climate Change in the 70s," online here. BACK

31. Elliott (1977-89), 18 June 1982; Keeling (1998), pp. 60-61, 66; Keeling et al. (1989), pp. 231-32. BACK

32. Nisbet (2007), p. 790; Keeling (2008), p. 1772. BACK

33. Tollefson (2013); Bell (2021), note, p. 291. BACK

copyright © 2003-2024 Spencer Weart & American Institute of Physics