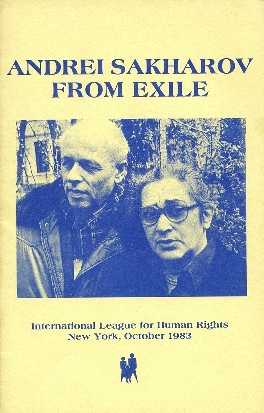

Andrei Sakharov From Exile

Texts provided by the International League for Human Rights New York, October 1983

I shall continue to live in the hope that goodness will finally triumph.

– Andrei Sakharov (Gorky, January 24, 1982)

We need reform, not revolution. We need a flexible, pluralist, tolerant society, which selectively and experimentally can foster a free, undogmatic use of the experiences of all kinds of social systems. What is detente? What is rapprochement? We are concerned not with words, but with a willingness to create a better and more decent society, a better world order.

...Other civilizations, including more successful ones, may exist an infinite number of times on the preceding and the following pages of the Book of the Universe. Yet we should not minimize our sacred endeavors in this world, where, like faint glimmers in the dark, we have emerged for a moment from the nothingness of dark unconsciousness into material existence. We must make good the demands of reason and create a life worthy of ourselves and of the goals we only dimly perceive."

– Nobel Prize lecture, 1975

Table of Contents

Introduction

An Autobiographical Note

Banishment

The Unlawful Nature of Exile

Life in Exile

Elena Bonner

Importance of Human Rights

The Human Rights Movement in the USSR

The Responsibility of Scientists

Internal Problems

Danger of War

Nuclear Disarmament

Poland and Solidarity

The Helsinki Final Act

How Can You Help the Sakharovs?

Elena Bonner’s Appeal

Andrei Sakharov: A Bibliography

The International League of Human Rights

Return to Exile in Gorky: 1980-1986

Introduction

In this small pamphlet are words of Andrei Sakharov. Andrei Sakharov: physicist, human rights defender, husband, father, grandfather, Nobel Peace laureate. His Nobel Peace citation called him "spokesman for the conscience of mankind." True.

These are only a few of his words on current issues. All of them are written from his place of banishment, the city of Gorky, in the Soviet Union. But words such as these cannot be confined to Gorky. They are heard in many places, in many nations. Hopefully, this pamphlet will make them heard even more.

Not only his words here, but all of his works should be read. His concerns are humanity’s concerns, his call is for human dignity and worth. His message is for men and women everywhere.

Why should Andrei Sakharov be forced to live in exile, harassed by police agents, denied the solace of family, children, and colleagues, and deprived of freedom and dignity? It is wrong. And all of us must bear witness to this wrong.

The International League for Human Rights has published this pamphlet to underscore the wrong done to Andrei Sakharov and to plead once again for his release. The League and Sakharov have long been friends and colleagues. Twelve years ago, the Moscow Human Rights Committee, founded by Dr. Saharov, Valery Chalidze, and Andrei Tverdokhlebov, joined the League as an affiliate. Dr. Sakharov and then League President John Carey regularly exchanged views by telephone on a wide range of human rights issues. In 1973, Dr. Sakharov was awarded the League’s Human Rights Award and in 1976, he was elected an Honorary Vice-President. Once he communicated with us often; now his words come to us with great difficulty and after long silences. Still, our association continues. We need his wisdom, his hope, his courage.

We need Andrei Sakharov. And he needs us. Quiet diplomacy and publicity do help. Simas Kudirka, Vladimir Bukovsky, Edward Kuznetsov, and the Vashchenko family are a few of those who have been rescued by a combination of public witness and government negotiations. A forceful letter from Philip Handler, then President of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, to his Soviet counterpart. helped to bring to an end a 1973 press campaign directed against Dr. Sakharov. The Sakharovs’ 1981 hunger strike and the worldwide support which it aroused won permission for their daughter-in-law, Liza Alexeyeva, to join her husband in Massachusetts. The world attention to Dr. Sakharov’s principles has undoubtedly deterred more severe measures against his person.

Dr. Sakharov is a symbol of human freedom. But he is also a human being who deserves to live with his family in freedom and dignity. Dr. Sakharov is 62 years old. He suffers from a heart condition. Action now on Dr. Sakharov’s case could avert an irrevocable tragedy. Let the voice of millions go forth, calling, demanding, pleading for the release of Andrei Sakharov. Release now.

Reader, consider now, the words of Andrei Sakharov. Are they not the words of the free human spirit?

—Jerome J. Shestack President

Please write or call the International League for Human Rights (236 East 46th Street, New York, NY 10017, USA, telephone 212-972-9554) if you wish additional information on Dr. Sakharov.

An Autobiographical Note

I was born on May 21, 1921, in Moscow. My father was a well-known physics teacher and the author of textbooks and popular science books. My childhood was spent in a large communal apartment most of whose rooms were occupied by our relatives, with only a few outsiders mixed in. Our home preserved the traditional atmosphere of a numerous and close-knit family--respect for hard work and ability, mutual aid, love for literature and science.

In 1945 I became a graduate student at the Lebedev Physical Institute. My adviser, the outstanding theoretical physicist Igor Tamm, who later became a member of the Academy of Sciences and a Nobel laureate, greatly influenced my career. In 1948 I was included in Tamm’s research group, which developed a thermonuclear weapon. I spent the next twenty years continuously working in conditions of extraordinary tension and secrecy, at first in Moscow and then in a special research center. We were all convinced of the vital importance of our work for establishing a worldwide military equilibrium, and we were attracted by its scope.

In 1950 I collaborated with Igor Tamm on some of the earliest research on controlled thermonuclear reactions. We proposed principles for the magnetic thermal isolation of plasma. The tokamak system, which is under intensive study in many countries, is closely related to our early ideas.

In 1953 I was elected a member of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

My social and political views underwent a major evolution over the fifteen years from 1953 to 1968. In particular, my role in the development of thermonuclear weapons from 1953 to 1962, and in the preparation and execution of thermonuclear tests, led to an increased awareness of problems engendered by such activities. In the late 1950s I began a campaign to halt or to limit the testing of nuclear weapons. This brought me into conflict first with Nikita Khrushchev in 1961, and then with the Minister of Medium Machine Building, Efim Slavsky, in 1962. I helped to promote the 1963 Moscow treaty banning nuclear weapon tests in the atmosphere, in outer space, and under water. From 1964, when I spoke out on problems of biology, and especially from 1967, I have been interested in an everexpanding circle of questions. In 1967 I joined the Committee for Lake Baikal. My first appeals for victims of repression date from 1966-67.

The time came in 1968 for the more detailed, public, and candid statement of my views contained in the essay "Thoughts on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence, and Intellectual Freedom." These same ideas were echoed seven years later in the title of my Nobel lecture: "Peace, Progress, and Human Rights." I consider these themes of fundamental importance and closely interconnected. My 196~ essay was a turning point in my life. It quickly gained worldwide publicity. The Soviet press was silent for some time, and then began ta refer to the essay very negatively. Many critics, even sympathetic ones, considered my ideas naive and impractical. But it seems ta me, thirteen years later, that these ideas foreshadowed important new directions in world and Soviet politics.

After 1970, the defense of human rights and of victims of political repression became my first concern. My collaboration with Valery Chalidze and Andrei Tverdokhlebov, and later with Igor Shafarevich and Grigorii Podyapolsky, on the Moscow Human Rights Committee was one expression of that concern.

After my essay was published abroad in July 1968, I was barred from secret work and excommunicated from many privileges of the Soviet establishment. The pressure on me, my family, and my friends increased in 1972, but as I came to learn more about the spreading repressions, I felt obliged to speak out almost daily in defense of one victim or another. In recent years I have continued to speak out as well on peace and disarmament, on freedom of association, movement, information, and opinion, against capital punishment, on protection of the environment, and on nuclear power plants.

In 1975 I was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. This was a great honor for me, as well as recognition for the entire human rights movement in the USSR.

Since the summer of 1969 I have been a senior scientist at the Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Physics. My current scientific interests are elementary particles, gravitation, and cosmology.

I am not a professional politician. That is why I am always bothered by questions concerning the usefulness and eventual results of my actions. I am inclined to believe that moral criteria in combination with unrestricted inquiry provide the only possible compass for these complex and contradictory problems. I shall refrain from specific predictions, but today as always I believe in the power of reason and the human spirit.

Banishment

On January 22, 1980 I was detained on the street and taken by force to the USSR Procurator’s Office. First Deputy Procurator General Alexander Rekunkov informed me that a decree of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet had deprived me of the title of Hero of Socialist Labor and of all other decorations and awards. I was asked to return the medals, orders, and certificates, but I refused, believing I had been given them for good reason. Rekunkov also informed me of the decision to banish me to the city of Gorky which is off limits for foreigners.

I was taken that same day on a special flight to Gorky together with my wife, Elena Bonner, who was allowed to accompany me. The Deputy Procurator of Gorky explained the terms of the regimen decreed for me: overt surveillance, prohibition against leaving the city limits, prohibition against meeting with foreigners and "criminal elements", prohibition against correspondence and telephone conversations with foreigners, including scientific and purely personal communications, even with my children and grandchildren. I was instructed to report three times a month to the police, and threatened that I would be taken there by force if I failed to obey.

The Unlawful Nature of Exile

The Soviet press, Soviet representatives abroad, and some of my Soviet colleagues during foreign missions, in contacts with people in the West who are concerned about my fate, in an attempt to disorganize my defense, assert that I am against detente, have spoken out against SALT, and have even permitted the divulgence of state secrets; they also emphasize the mildness of the measures taken against me. My attitude and open way of life and actions are well known and show how absurd these accusations are.

I have never infringed state secrecy, and any talk of this is slander. I regard thermonuclear war as the main danger threatening mankind, and consider that the problem of preventing it takes priority over other international problems; I am in favor of disarmament and a strategic balance, I support the SALT-II agreement as a necessary stage in disarmament negotiations. I am against any expansion, against Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, but in favor of aid to refugees and the starving throughout the world. I regard as very important an international agreement on refusal to be the first to use nuclear weapons, concluded on the basis of a strategic balance in the field of conventional weapons. I am convinced of the interrelatedness of international security and defense of human rights, and am in favor of freedom of convictions and exchange of information, freedom to choose one’s country of domicile and place of domicile within that country, and freedom of religion. I am deeply anxious about the fate of political prisoners in the USSR, unjust courts, illegal repression. The most important aim for me is the release of prisoners of conscience throughout the world, including the USSR, the countries of Eastern Europe, and China.

I do not make it my task to give special support to the viewpoints of Western governments, or anyone else, but express precisely my own viewpoint on matters causing me anxiety. As for the mildness of the measures taken against me, they are not as severe as the terms of imprisonment lasting many years for my friends and scientists--prisoners of conscience Sergei Kovalev, Yury Orlov, Anatoly Shcharansky, Tanya Velikanova, Viktor Nekipelov, Aleksandr Lavut, Tanya Osipova, and many others.

But my banishment, without trial in infringement of all constitutional guarantees, the isolation measures applied, interference of the KGB in my life, are completely illegal and inadmissible as an infringement of my personal rights, and as a dangerous precedent of the actions of the authorities, who are casting aside even that pitiful imitation of legality in the persecution of dissidents that they displayed in recent years. Only a court has the right to establish that a law has been infringed and to define the manner of punishment. Any deliberations about culpability and mercy without a trial are inadmissible and against a person’s rights.

I direct particular attention to Perelygin’s assertion that the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet decreed my regimen. I have repeatedly asked the USSR Procurator General Rekunkov and Perelygin, the Deputy Prosecutor of the Gorky region, to show me a document confirming that assertion and indicating the date and signature on the decree ordering my removal by force to Gorky, my isolation and my regimen here, but no such document has been produced. The Vedemosti (Gazette) of the Supreme Soviet has published only the decree of January 8, 1980, revoking my government awards. A decree ordering my regimen would doubtless be unconstitutional. Perelygin is a lawyer and should know that the use of the term "regimen" with regard to my status is illegitimate. Only a court can impose a regimen, specifying its nature in the verdict pronounced on a defendant. I have not been the subject of a legal procedure. I have not been accused of a crime and no one has sentenced me.

I have been isolated in Gorky and deprived of my constitutional right to a fair trial (if grounds for a trial exist). I have also been deprived of: the inviolability of my home; my freedom of thought and expression; unhindered correspondence and telephone conversations; treatment by a doctor of my choice; my right to rest; even my right to leave this city. I refuse to believe that the Presidium issued such a decree. I believe that Perelygin is in fact blackmailing me with the implicit threat of harsher repression and new crimes. My banishment from Moscow, my isolation, the simple burglaries followed by the theft involving drugs were all illegal, but they have happened. What is to prevent the use of drugs again and some terrible new crime?

I have been forced to live away from my home and under restraint for almost three years, a period more than sufficient for any investigation and exceeding the terms of punishment specified for many offenses by the Criminal Code. The Soviet press and official Soviet representatives in their contacts with my colleagues abroad and Western statesmen and public personalities portray my illegitimate and arbitrary treatment as stemming from humanitarian motives. But humane law cannot be the source of tyrannical acts.

I have reported Perelygin’s warning, his vague reference to an un published decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, and his new threats in the hope that world public opinion will speak out against my illegal exile and isolation. I ask the government leaders in States signing the Helsinki Final Act, public personalities, and my scientific colleagues abroad to defend me on legal and humanitarian grounds and to oppose new acts of repression.

Life in Exile

I live in an apartment with a policeman stationed at the door round-the-clock. I often live completely alone, since my wife is forced to spend a great deal of time in Moscow.

I spend most of the day at my desk, reading and writing. In order to listen to Voice of America and other Western radio stations I have to go far from the house to escape my own personal jamming system, but the regular jamming is sufficiently strong that often I still can’t hear anything. Household chores take up some time--I often straighten up the apartment before my wife’s arrival, I go and buy bread, and I take my wash to the laundry. You must remember that I do all these things quite slowly. I hardly ever take walks when my wife is away, but when she is here, we go for walks, sometimes we go to the movies, and three times in the past year and a half we attended concerts by Shafran, Richter, and Gilels when they came to Gorky.

My wife and I normally cannot communicate with the West by telephone. This is especially hard for us, since our children live in America. Our letters often fail to get through. (They are illegally seized by the KGB.)

I still receive some scientific mail from the West, but probably not all of it. I am deeply grateful to my correspondents, but I don’t receive personal letters. I didn’t receive a single letter of congratulations from the West on my 60th birthday, not even from our children. To give you an example of the KGB’s pettiness, on May 16 1 sent a telegram to my friends who had gathered in our Moscow apartment to celebrate my 60th birthday, but that telegram wasn’t delivered until the following evening. Many domestic telegrams sent to me, or that I send, never reach their destination. The same is true for letters.

I wish to devote the major part of my energy to scientific work. But it is simply impossible to talk of "quiet scientific work" when I am kept isolated in illegal exile and the repeated thefts of my scientific and other manuscripts require me to spend enormous energy simply restoring those works.

Elena Bonner included the following passage in a letter written in November 1982:

It will soon be three years since Andrei has been living in detention, deprived of medical care (it was made clear during our hunger strike that only "reliable" doctors will be permitted to treat us in Gorky), deprived of rest, of the right to leave the city, virtually deprived of the right to think or write, the right to free scientific and human contacts, the right to correspond, to talk over the telephone, and many other things without which his life is painful. He is miserable without the opportunity to phone some colleague and discuss an integral equation when the thought occurs . . . Andrei so lacks the atmosphere of science that he even talks to me about physics, and it would be difficult to find a less qualified audience. The days of absolute loneliness when I am forced to be in Moscow are particularly trying for him. Sometimes I must be away for days.

Elena Bonner

This article is being taken to Moscow by my wife, my constant helper, who shares my exile and willingly takes upon herself the heavy burdens of traveling back and forth, handling my communications with the outside world, coping with the growing hatred of the KGB. Earlier, she withstood the poison of slander and insinuation, focused more on her than on me. The fact that I am Russian and my wife is half-Jewish has proved useful for the purposes of the KGB.

Every time my wife leaves, I do not know whether she will be allowed to travel without hindrance and to return safely. My wife, although formally not under detention, is in greater danger than I am. I urge those who speak out on my behalf to keep this in mind. It is impossible to forsee what awaits us. Our only protection is the spotlight of public attention on our fate by friends around the world.

The Importance of Human Rights

The most important conditions for international trust and security are the openness of society, the observation of the civil and political rights of man--freedom of information, freedom of religion, freedom to choose one’s country of residence (that is, to emigrate and return freely), freedom to travel abroad, and freedom to choose one’s residence within a country.

The human rights proclaimed by the Universal Declaration in 1948, and again confirmed by the Helsinki Accord in 1975 as being part and parcel of international security, are rights which continue to be flagrantly violated in the USSR and in other countries, particularly those of Eastern Europe. It is necessary to defend the victims of political repression (within a country and internationally, using diplomatic means and energetic public pressure, including boycotts). It is also necessary to support the demand for amnesty for all prisoners of conscience, all those who have spoken out for openness and justice without using violence. The abolition of the death penalty and the unconditional banning of torture and the use of psychiatry for political purposes are also necessary. Other necessities include the demand for a series of legislative and administrative measures, including the abolition of censorship, the facilitation of travel, and so on. I turn for support for these demands to my colleagues in science, Soviet and Western; to the public figures and statesmen of all countries; to the people of the entire world. The governments and the public of all countries must insist on the unconditional and complete fulfillment of the humanitarian obligations the USSR has taken upon itself, in particular, in the United Nations’ International Covenants on Human Rights and in the Helsinki Accord. This is a condition for being able to trust the signature of the USSR.

The Human Rights Movement in the USSR

The moral significance of the human rights movement, which arose in the middle of the 1960s has been enormous, although the movement itself is small in number and deliberately apolitical. It has changed the moral climate and created the spiritual preconditions needed for democratic changes in the USSR and for the formulation of an ideology of human rights throughout the world. Dangerous illusions about the nature of our system, which used to be almost universal among Western intellectuals, have become much less prevalent and, in fact, have almost disappeared. I myself felt the attraction of the human rights movement in the mid-1960s. It deeply affected my attitudes and my public activities.

I do not think that many human rights advocates expected that the regime would recognize the justice of our appeals. The fact that we addressed the authorities was simply a natural reflection of our aspiration for a rule of law, of our loyalty to the state, of our confidence that we were in the right legally as well as ethically. People perhaps hoped there might be some results in particular cases for specific individuals. That is different from change in the regime’s policies.

I do not believe that the authorities were frightened by radical demands. The main body of dissidents was hardly radical: does a request to allow the Tatars’ return to the Crimea or to release someone from a psychiatric hospital threaten the foundations of the state? The authorities simply opposed any display of independence or the circulation of information inside the country or to the West. But for our part we could no longer live as we had in the past.

We enter the 80s under difficult conditions. Exploiting the general aggravation of the international situation, the Soviet authorities have launched a major attempt to eliminate dissidence both in Moscow and in the provinces. The attack is aimed against the human rights movement as a whole as well as against independent samizdat journals including A Chronicle of Current Events, against the Helsinki Monitoring Groups, and the associated commissions on psychiatric and religious problems.

Religious persecutions have been intensified, the number of emigration visas have been cut back sharply, the persecutions against Crimean Tatars have been stepped up. The action against me is only part of a widespread campaign against dissidents. Its immediate cause was probably my statement about events in Afghanistan; but I believe it was in the works for a long time.

The Responsibility of Scientists

I appeal to scientists everywhere to defend those who have been repressed. I believe that in order to protect innocent persons it is permissible and, in many cases, necessary to adopt extraordinary measures such as the interruption of scientific contacts or other types of boycotts. I urge the use, as well, of all the possibilities of publicity and of diplomacy. In addressing the Soviet leaders, it is important to take into account that they do not know about most letters and appeals directed to them. Therefore, personal interventions by Western officials who meet with their Soviet counterparts have particular significance. Western scientists should use their influence to press for such interventions.

I hope that carefully thought out and organized actions in defense of victims of repression will ease their lot and add strength, authority, and energy to the international scientific community.

I have called this statement "The Responsibility of Scientists." Tatiana Velikanova, Yury Orlov, Sergei Kovalev, and many others have decided this question for themselves by their active, self-sacrificing struggle for human rights and for an open society. Their sacrifices have been enormous, but they have not been in vain. These individuals are improving the ethical image of our world.

Many of their colleagues who live in totalitarian countries but who have not found within themselves the strength for such struggle, do try to fulfill honestly their professional responsibilities. It is, in fact, essential to work at one’s profession. But has not the time come for those scientists, who often exhibit their perception and conformity when with close friends, to demonstrate their sense of responsibility in some fashion which has more social significance, and to take a more public stand, at least on issues such as the defense of their persecuted colleagues and control over the faithful execution of domestic laws and the performance of international obligations? Every true scientist should undoubtedly muster sufficient courage and integrity to resist the temptation and the habit of conformity. Unfortunately, we are familiar with too many counterexamples in the Soviet Union, sometimes using the excuse of protecting one’s laboratory or institute (usually just a pretext), sometimes for the sake of one’s career, sometimes for the sake of foreign travel (a major lure in a closed country such as ours]. And was it not shameful for Yury Orlov’s colleagues to expel him secretly from the Armenian Academy of Sciences while other colleagues in the USSR Academy of Sciences shut their eyes to the expulsion and also to his physical condition? ... Many active and passive accomplices in such affairs may themselves someday attract the growing appetite of Moloch. Nothing good can come of this. Better to avert it.

Western scientists face no threat of prison or labor camp for public stands; they cannot be bribed by an offer of foreign travel to forsake such activity. But this in no way diminishes their responsibility. Some Western intellectuals warn against social involvement as a form of politics. But I am not speaking about a struggle for power--it is not politics. It is a struggle to preserve peace and those ethical values which have been developed as our civilization evolved. By their example and by their fate, prisoners of conscience affirm that the defense of justice, the international defense of individual victims of violence, the defense of mankind’s lasting interests are the responsibility of every scientist.

Internal Problems

I have taken a fresh look at the economic difficulties and food shortages in the USSR, at the privileges of the bureaucratic and Party elite, at the stagnation of our industry, at the menacing signs of the bureaucracy preventing and deadening the life of the entire country, at the general indifference to work done for a faceless state (nobody could care less), at corruption and improper influence, at the compulsory hypocrisy which cripples human beings, at alcoholism, at censorship and the brazen Iying of the press, at the insane destruction of the environment, the soil, air, forests, rivers, and lakes. The necessity for profound economic and social reforms in the USSR is obvious, but attempts to carry them out encounter the resistance of the ruling bureaucracy and everything goes on as before, with the same worn-out slogans. Occasionally something new is tried, but successes are rare. Meanwhile the military-industrial complex and the KGB are gaining in strength, threatening the stability of the entire world; and super-militarization is eating up all our resources.

My ideal is an open pluralistic society which safeguards fundamental civil and political rights, a society with a mixed economy which would permit scientifically-regulated, balanced progress. I have expressed the view that such a society ought to come about as a result of the peaceful convergence of the socialist and capitalist systems and that this is the main condition for saving the world from thermonuclear catastrophe.

The era of the Stalin regime’s monstrous crimes represents half of our country’s history. Although Stalin’s actions have been officially condemned, the specific crimes and the scope of repressions under Stalin are carefully hidden and those who expose them are prosecuted for alleged slander. The terror and famine, accompanying collectivization, Kirov’s murder and the destruction of the cultural, civil, military, and party cadres, the genocide occuring during the resettlement of "punished" peoples, the penal camps and the deaths of many millions there, the flirtation with Hitler which turned into a national tragedy, the repression of prisoners of war, the laws against workers, the murder of Mikhoels and the resurgence of official antisemitism, all these evils should be completely disclosed. A people without historical memory is doomed to degradation.

Danger of War

A major change has occurred in the world balance of forces, and this change is intensifying. It is true, of course, that the development of new technology and the growth in number of weapons have not been confined to the Soviet Union. This is a mutually stimulating process in virtually all technologically developed countries. In the United States, in particular, such developments have perhaps proceeded on a higher scientific-technological level and this, in turn, caused alarm in the Soviet Union.

But in order to assess the situation properly it is imperative to take note of the particular features of the Soviet Union--a closed totalitarian state with a largely militarized economy and bureaucratically centralized control, all of which make the growing might of such a country even more dangerous. In more democratic societies, every step in the field of armaments is subjected to public budgetary and political scrutiny and is carried out under public control. In the Soviet Union, all decisions of this kind are made behind closed doors and the world learns of them only when confronted by faits accomplis. Even more ominous is the fact that this situation applies also to foreign policy, involving issues of war and peace.

At the same time that the change in the balance of forces was occurring--though not only because of that change--there was both covert and overt Soviet expansion in key strategic and economic regions of the world. Southeast Asia (where Vietnam was used as a proxy) and Angola (with Cuba as the proxy), Ethiopia, and Yemen are some of the examples.

The most acutely negative manifestation of Soviet policies was the invasion of Afghanistan which began in December 1979 with the murder of the head of state. Three years of appallingly cruel anti-guerrilla war have brought incalculable suffering to the Afghan people, as attested by the more than four million refugees in Pakistan and Iran.

It was precisely the general upsetting of world equilibrium caused by the invasion of Afghanistan and by other concurrent events which was the fundamental reason that the SALT II agreement was not ratified.

Nuclear Disarmament

Today we ask ourselves once again: Does mutual nuclear terror serve as a deterrent against war? For almost 40 years the world has avoided a third world war. And, quite possibly, nuclear deterrence has been, to a considerable extent, the reason for this. But I am convinced that nuclear deterrence is gradually turning into its own antithesis and becoming a dangerous remnant of the past. The equilibrium provided by nuclear deterrence is becoming increasingly unsteady; increasingly real is the danger that mankind will perish if an accident or insanity or uncontrolled escalation draws it into a total thermonuclear war. In light of this it is necessary, gradually and carefully, to shift the functions of deterrence onto conventional armed forces, with all the economic, political, and social consequences this entails. It is necessary to strive for nuclear disarmament. Of course, in all the intermediate stages of disarmament and negotiations, international security must be provided for, vis-a-vis any possible move by a potential aggressor. For this in particular one has to be ready to resist, at all the various possible stages in the escalation of a conventional or a nuclear war. No side must feel any temptation to engage in a limited or regional nuclear war.

I agree that if the "nuclear threshold" is crossed, i.e., if any country uses a nuclear weapon even on a limited scale, the further course of events would be difficult to control and the most probable result would be swift escalation leading from a nuclear war initially limited in scale or by region to an all-out nuclear war, i.e. to general suicide.

It is relatively unimportant how the "nuclear threshold" is crossed--as a result of a preventive nuclear strike or in the course of a war fought with conventional weapons, when a country is threatened with defeat, or simply as a result of an accident (technical or organizational).

In view of the above, I am convinced that the following basic tenet... is true: Nuclear weapons only make sense as a means of deterring nuclear aggression by a potential enemy, i.e., a nuclear war cannot be planned with the aim of winning it. Nuclear weapons cannot be viewed as a means of restraining aggression carried out by means of conventional weapons.

Of course... this last statement is in contradiction to the West’s actual strategy in the last few decades. For a long time, beginning as far back as the end of the 1940s, the West has not been relying on its "conventional" armed forces as a means sufficient for repelling a potential aggressor and for restraining expansion. There are many reasons for this--the West’s lack of political, military, and economic unity; the striving to avoid a peacetime militarization of the economy, society, technology, and science; the low numerical levels of the Western nations’ armies. All that at a time when the USSR and the other countries of the socialist camp have armies with great numerical strength and are rearming them intensively, sparing no resources. It is possible that for a limited period of time the mutual nuclear terror had a certain restraining effect on the course of world events. But, at the present time, the balance of nuclear terror is a dangerous remnant of the past! In order to avoid aggression with conventional weapons one cannot threaten to use nuclear weapons if their use is inadmissible. One of the conclusions that follows here--and a conclusion you draw--is that it is necessary to restore strategic parity in the field of conventional weapons. This you expressed somewhat differently, and without stressing the point.

Meanwhile this is a very important and non-trivial statement which must be dwelt on in some detail.

The restoration of strategic parity is only possible by investing large resources and by an essential change in the psychological atmosphere in the West. There must be a readiness to make certain limited economic sacrifices and, most important, an understanding of the seriousness of the situation and of the necessity for some restructuring. In the final analysis, this is necessary to prevent nuclear war, and war in general. Will the West’s politicians be able to carry out such a restructuring? Will the press, the public, and our fellow scientists help them ~and not hinder them as is now frequently the case)? Can they succeed in convincing those who doubt the necessity of such restructuring? A great deal depends on it--the opportunity for the West to conduct a nuclear arms policy that will be conducive to the lessening of the danger of nuclear disaster.

Poland and Solidarity

A movement involving ten million people, conscious of their rights and of their strength, and fighting for a better life, for a more just, viable, and pluralistic society within the existing framework, cannot disappear without a trace, no matter how depressing and complicated the present situation may be.

The stand taken by the majority of Solidarity’s leaders and supported by millions of workers, peasants, and intellectuals, and even by many members of the Polish United Workers (Communist) Party serves the interests of Poland and does not threaten the fundamental principles of Poland’s system or, still less, neighboring states. I remain convinced that the future belongs to an evolving pluralism and to an open society, the only kind which can be flexible, viable, and compatible with international security. Hopefully, events in Poland will prove me right.

The Helsinki Final Act

The critical international situation requires that the Western participating states coordinate their tactics and pursue their goals with more determination and consistency than at Belgrade. The Helsinki Accords, like detente as a whole, have meaning only if they are observed fully and by all parties. No country should evade a discussion on its own domestic problems, whether the problems of Northern Ireland, the Crimean Tatars, or Sakharov’s exile (here I am speaking objectively). Nor should a country ignore violations in nther participating states. The whole point of the Helsinki Accords is mutual monitoring, not mutual evasion of difficult problems.

How can you help the Sakharovs?

The following letter by colleagues of Dr. Sakharov circulated in Moscow samizdat inJanuary 1983. While primarily addressed to scientists, its suggestions are relevant for all who wish to assist the Sakharovs.

How can you help Sakharov? Appeal to the top Soviet leaders in a way which will not permit the KGB simply to file and forget your protests. Actions speak louder than words when trying to impress the mammoth Soviet bureaucracy. Fortunately, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences understands this. The U. S. Academy’s decisive action in the spring of 1980 forced the KGB to change thelr tune from "the traitor Sakharov deteriorated as a scientist long ago" to "Academician Sakharov has every opportunity for scientific work in Gorky." (The U.S. Academy’s action may have saved Dr. Sakharov’s life.)

For the last three years the KGB has been forced to report on the boycott’s effectiveness. Foreign scientists invited to the Soviet Union should keep in mind that their visits will be used to show that "Sakharov is forgotten" and that Western scientists accept his exile. (Their names will be cited without their knowledge or consent. Concern for Sakharov’s fate expressed in private conversation with Soviet officials is not sufficient to prevent this happening.)

Open appeals to the government and to the Academy sent by registered mail from Moscow and published in the Western press can prevent the secret police from speculation with the names of foreign visitors. (Publication of a letter after the visitor has returned home is an alternative, but it is less effective.)Something useful may result if copies of appeals are circulated to foreign correspondents in Moscow (the KGB presumably reports such actions) and delivered to Academy officials and other Soviet scientists. (This approach should also be used to help Orlov, Shcharansky, and other human rights advocates).

Academy officials--president Alexandrov, vice-president Velikhov, Kotelnikov, Logunov, and Ovchinnikov--enjoy direct access to the government and could discuss Sakharov’s situation with the head of the KGB. Academicians N.G. Basov and Gury Marchuk enjoy similar influence. Basov, a Nobel laureate and director of the Institute of Physics, was made a member of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet in November 1982 at the same time as Yury Andropov. Marchuk is a deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers and Chairman of the State Committee for Science and Technology. Marchuk recently conducted important negotiations in France and was received by President Mitterand on January 12. (Did Mitterand risk questioning Marchuk about the situation of Sakharov and other repressed scientists?)

Soviet scientists also react to deeds which affect them directly and not to words. It is essential, therefore, to mention international cooperation which benefits Soviet research on the peaceful use of thermonuclear energy. Academician Sakharov, together with the late Igor Tamm, was a pioneer in the field. The authorities’ treatment of Sakharov is hardly consonant with international scientific cooperation. Letters and appeals on behalf of Sakharov must stress again and again his contributions to basic research. Thus, since Pravda published an article ("Secrets of Matter", January 23, 1983) on proton decay. Soviet leaders should be reminded of Sakharov’s prophetic work on this problem.

Can we let a man like Sakharov suffocate in Gorky? His exile and detention resemble the ordeal of the American hostages in Iran. He can be freed as the American diplomats were. Sakharov should be able to lead a normal life, to attend scientific seminars, to resume his scientific contacts, to be treated by the Academy of Sciences’ doctors, and to participate in the Academy’s sessions since he has been a member for thirty years. Sakharov should be allowed to return to his home in Moscow or, at the very least, to his house in the country nearby.

Elena Bonner's Appeal

I write these words out of concern for my huband. This is not easy for me, but I am uncertain, and worried about his fate.

In my ten years of life with Andrei Sakharov we have had many guests from the West. I appeal to them: the Germans and Americans, French and English, Norwegians and Swedes, Italians and Spaniards, Dutch and Japanese who have visited us. Over the years I have begun to feel that we have friends everywhere: those who have shared tea with us in our kitchen or crowded living room; those who have read my husband’s books or talked to him about detente, disarmament, SALT, nuclear energy, environmental protection; about the right to choose one’s country of residence; about freedom of conscience; and about those who have tried to break down the wall of silence and have paid for it with years of prison, camp, exile, and psychiatric hospitals.

You businessmen and politicians, journalists and scientists, and simply private persons who have come to see Russia and Sakharov: I don’t have to tell you what kind of a man he is. You have seen him and you have spoken with him. I appeal to you to testify under oath--in the courts, before government and private commissions--on your conversations with Andrei Sakharov, on what he has said and written about today’s most pressing problems. My husband’s life depends upon your memories of him and your persistence. He is denied a hearing in court, and if you forget him and fall silent, the authorities will finish their planned retaliation, caring little about appearances. I call upon you to become a witness for the defense.

I appeal to scientists. Andrei has spoken of so many of you with such love and enthusiasm that his feelings have rubbed off on me as well. We are filled with joy when the radio brings us the voices of western scientists. We believe that these voices will not fall silent until Andrei Sakharov’s right to think, speak, and live as a free man is restored.

Andrei Sakharov: A Bibliography

Four volumes of Andrei Sakharov’s statements on public issues have been published in the United States:

Progress, Coexistence, and Intellectual Freedom (Norton 1968)

Sakharov Speaks (Knopf 1974)

My Country and the World (Knopf 1975)

Alarm and Hope (Knopf 1978)

On Sakharov (Knopf 1982), based on a Festschrift compiled in Moscow, contains several articles written by Sakharov since 1978.

A. D. Sakharov: Collected Scientific Works (Marcel Dekker, New York, 1982) contains English translations of Sakharov’s scientific papers with commentary by Sakharov himself and Western physicists.

The autobiographical note and several other items in this collection are abridged from On Sakharov.

Sakharov’s statements on disarmament are excerpted from Foreign Affairs, summer 1983, and Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, June-July 1983.

Many of Sakharov’s statements and appeals have appeared in A Chronicle of Human Rights in the USSR published quarterly by Khronika Press in New York from 1973 to 1983.

The International League for Human Rights

The International League for Human Rights appreciates the assistance of Khronika Press in editing this publication.

The International League for Human Rights, founded in 1942, is among the oldest of the international organizations concerned with the promotion and protection of human rights. The League addresses the full range of human rights, taking as its platform the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in 1948.

At the heart of the League’s activity is its casework program for victims of human rights abuse. Through its Defenders Project, the League seeks to protect courageous advocates of human rights in repressive societies, such as Andrei Sakharov. The League also acts to reunify families separated by political borders, prevent torture and other abuses against individuals, secure redress for the families of the disappeared, and assist victims of religious and racial discrimination.

The League works with 40 affiliates in 30 countries worldwide and has consultative status with the United Nations (ECOSOC), UNESCO, the Council of Europe, and the International Labor Organization. It cooperates with regional organizations such as the Organization of American States.

As a membership organization, the League depends solely on the support of public-spirited persons and institutions which believe in safeguarding international human rights. As a matter of principle, the League accepts no funds from any governmental or intergovernmental organization.

For additional copies, contact: International League for Human Rights 236 E. 46th Street, 5th Floor New York, N.Y. 10017, USA 212-972-9554