COCKE: It pretty well convinced people and convinced us, too, that pulsars were indeed not white dwarfs but rather neutron stars. And then finally—I think maybe a month later—the discovery of the radio pulses from the general direction of the Crab Nebula was announced.

DISNEY: What was more, they discovered that this pulsar was pulsing about 30 times a second. So, it was even faster than the one they discovered in Australia.

COCKE: People were talking about it, wondering what in the world these things were, and why. And everyone was being rather astounded at the apparent connection with the Crab Nebula.

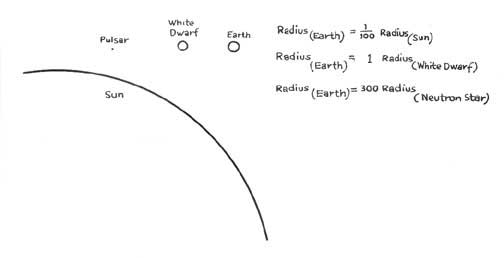

DISNEY: And the reason why everybody was excited was because it looked as if pulsars were the first actual sight of something which people had been prognosticating for thirty years—namely neutron stars. That's to say, objects which are made out of incredibly dense material—so dense that the usual analogy is that a teaspoonful of it would weigh a billion tons.

COCKE: Well, this was what really pinned it down for us, because what we then did was, we went to do a rather more thorough study of the Crab Nebula ourselves to see if we could pinpoint where, within the Nebula, the pulsar might be.

DISNEY: Radio telescopes don't have very good directional resolution. And, in fact, the uncertainty was so great that it could have been literally thousands of stars. So before we could look for a particular place, we got to make some guess—do some detective work as to where we should look. And, it seemed the logical place to start off was to look right in the center of the Nebula. I mean—what's supposed to happen in a supernova explosion is that once upon a time it was a star, and then the center of it collapsed to this neutron star and the outside is completely blown off.

|

| Crab Nebula; note that the picture alternates between two images made nearly 30 years apart, which illustrates the expansion of the Nebula with time. |

I remember asking a couple of very well known, very prominent astrophysicists, asking them whether or not they felt that the pulsar would ever be detected optically. And they all were very, very negative about it, and they said, "Oh, no, I doubt very much that will ever happen."