DISNEY: In fact, looking for pulsars in the optical is rather a complicated experiment, requires all sorts of equipment which we'd no idea about at the time. And Ray Weymann, who is one of the senior scientists at the Observatory, suggested to us that there was an ideal piece of equipment already in the Observatory belonging to Don Taylor. Now, Don Taylor is a bit of an electronic wizard. This little piece of equipment he had—which is a kind of a miniature computer—you can plug the signals in from the telescope onto it at once. And you can look at the screen and you can see all these little dots which show the signals coming in—the lights coming in. And you can watch it climbing up the screen, and, if it's pulsing, you'll see a little wave developing in the middle of the screen.

MORRISON: They knew the timing from the radio work—33.2 milliseconds, or something of the sort. Knowing that number was indispensable. They superposed the light that was coming—the weak light that was coming—by cutting it every 33 milliseconds and putting the light, folding it up every 33 milliseconds—folding it up and folding it up electronically—so it added up and the pulse slowly grew out of the noise. Because in a single pulse, their telescope didn't get enough photons in to make a smooth curve at all. It just got a jagged noisy appearance. It was just this superposition that made it possible.

DISNEY: So we decided to go in with Don Taylor, which was a hell of a good thing. We went up the mountain one night and took a photograph of the Crab Nebula so that we could pinpoint all these little stars that were in the center of it. They're far too faint for us to see with a tiny little telescope like a 36" telescope. So what we were going to have to do was to take a photograph on which you can see these stars; and then using a sort of automatic guider, it's called—it's a thing for setting the telescope off from a star that you can see to a piece of sky where the stars are too faint to see—you can do it automatically by steering the telescope to the place you want.

COCKE: We all went. All three of us went up to Kitt Peak, and Don Taylor and Bob McCallister, who is the night assistant, worked around with the electronics, I remember, while Disney and I turned our attention to the telescope itself.

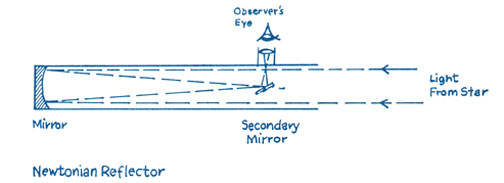

DISNEY: The Observatory in Arizona is on a very remote mountain peak inside an Indian reservation. And up on the top of the mountain you live in a little dormitory where you cook for yourself. So we had to get all our food, load all the equipment into the car at the University, and then drive out across the desert. And then ride up the mountain—this very spectacular winding road up the side of the mountain—to the very top where the Observatory is situated. And then, Don, who was keeping very close guard on all his equipment in case we did anything with it, carried it all up—we helped him—up into the dome. I should say, the telescope we were using was an old fashioned Newtonian telescope, where the light comes down and you have to work at the top end of it. So you climb up right underneath the dome, so you're working right up against the stars as it were, looking down inside the telescope—the top-end of the telescope. And all our equipment was up on the little mezzanine floor, which was up beside the top of the telescope.

Well, we got it all set up and we cooked ourselves a meal and then we went out into the dome. I didn't realize, to begin with, how cold it could be observing. So there I was sitting around in a sports jacket and freezing to death and regretting it like mad. It's very, very, very dark inside—of course, as it has to be—and so you lunge around with a torch [flashlight] in your hand. And of course you're not supposed to turn on the torch during the critical moments, because even the smallest piece of torch light can ruin the observations, ruin the observer's eyesight, and generally foul things up. So there you are walking around up on this high platform—with no guard rail on it, I might say—hoping to God you're not going to step off the edge, and hoping that you're not going to bang your head on all the sharp projections the telescope has on it.

And then, Don got all his electronics ticking over, and all the dials were reading the right thing. The lights were flashing and the voltages were all correct. And what we were doing was trying to learn to set the telescope on the right place in the Crab—that's the very center of it where Baade's Star was. And so we spent the whole of the first night making a bit of a hash of this.

COCKE: Well, it was very exciting, but I was quite nervous, and I had the distinct feeling of wondering, really, what in the hell I was doing there. The second night we actually did some observations.

DISNEY: John and I were doing two things: looking through the telescope measuring off distances, and calculating exactly where we were in the Nebula. And about 11 o'clock that night, I think, everything was going—we were set on the central object, we were all quite excited, and we were sure everything was all right. And then we switched it all on and watched this screen with all these little dots climbing up it. What we were looking for, was that several of these dots should race out in front of the others, because this would tell us it was a pulse of light coming from this pulsar.

|

Pcture of 36" telescope dome at Kitt Peak, taken in Winter, where the first official optical pulsar was discovered. The telescope is the one on the left. |