As soon as they realized that atoms can be split, physicists began to talk over the possible consequences. John Dunning recalls...

DUNNING: I well remember that on January 25, 1939 there was a session at the faculty

club at Columbia around the lunch table. Bohr had been talking very enthusiastically

about fission possibilities in Princeton and it seemed clear that this

had to be really got at. Immediately, the question arises as an experimentalist,

not a theorist, shouldn't there be secondary neutrons created? Or evaporated?

If there were enough of these, then the long-sought-for key to a self-sustaining

nuclear energy release might indeed be here. World War II was pretty clearly

in the offing at that time and all of us recognized the far-reaching consequences

that might be possible if fission could really be developed.

DUNNING: I well remember that on January 25, 1939 there was a session at the faculty

club at Columbia around the lunch table. Bohr had been talking very enthusiastically

about fission possibilities in Princeton and it seemed clear that this

had to be really got at. Immediately, the question arises as an experimentalist,

not a theorist, shouldn't there be secondary neutrons created? Or evaporated?

If there were enough of these, then the long-sought-for key to a self-sustaining

nuclear energy release might indeed be here. World War II was pretty clearly

in the offing at that time and all of us recognized the far-reaching consequences

that might be possible if fission could really be developed.

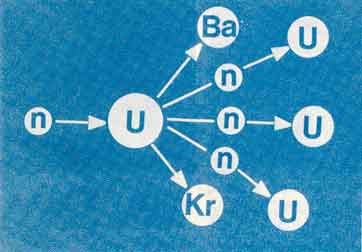

Being able to split uranium did not necessarily mean you could get a chain reaction and release a lot of energy. That question had to be answered before anything else. It was exactly the question that Leo Szilard had been asking for years. Now Szilard was in New York, another refugee from Fascism, and he was urging people to attack the problem. Herbert Anderson recalls...

ANDERSON:

Well, Fermi came back and the first thing he did when he came back to Columbia,

was he got hold of me, took me in the office, and then began to write down

on the blackboard all the experiments we ought to do. And, of course, the

thing that was the most important, if you were going to make a chain reaction,

is to make sure that neutrons come out. Of course, so far all that was known

is that a lot of energy is released. But Szilard had already pointed out

that to make a chain reaction you had to have more neutrons emitted than

were absorbed. But, of course, Fermi realized that the two fragments of

the fission would be very heavily neutron rich and it was quite likely that

there would be some extra neutrons boiled off in the process. And so, he

immediately designed an experiment which he wanted me to do with him to

see where the neutrons were emitted. And so, we launched on a career of

trying first of all to see whether neutrons were emitted and in what number.

Experiments were also being done (in fact, they always seemed to be about

a week or so ahead of us) by Joliot, Halban and Kowarski working in Paris.

ANDERSON:

Well, Fermi came back and the first thing he did when he came back to Columbia,

was he got hold of me, took me in the office, and then began to write down

on the blackboard all the experiments we ought to do. And, of course, the

thing that was the most important, if you were going to make a chain reaction,

is to make sure that neutrons come out. Of course, so far all that was known

is that a lot of energy is released. But Szilard had already pointed out

that to make a chain reaction you had to have more neutrons emitted than

were absorbed. But, of course, Fermi realized that the two fragments of

the fission would be very heavily neutron rich and it was quite likely that

there would be some extra neutrons boiled off in the process. And so, he

immediately designed an experiment which he wanted me to do with him to

see where the neutrons were emitted. And so, we launched on a career of

trying first of all to see whether neutrons were emitted and in what number.

Experiments were also being done (in fact, they always seemed to be about

a week or so ahead of us) by Joliot, Halban and Kowarski working in Paris.

The Paris team, like Fermi, knew that a chain reaction would come only on one condition: if each uranium atom, when it split, spat out fresh neutrons. Joliot asked Kowarski to try to think of a way to detect them..