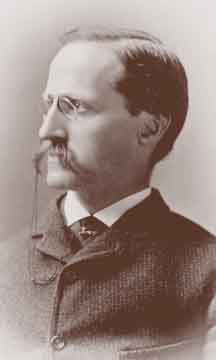

AUGUSTUS

ROWLAND

None struggled harder than Rowland. His boyhood and youth were spent in impassioned efforts to find the means and the freedom for fundamental research. He came from a long line of sturdy Protestant theologians (his great-grandfather had spoken from his pulpit against foreign oppression so zealously that during the War for Independence, when a British fleet invested Providence, he had to flee the city). Henry Rowland was expected to go into the ministry, but he preferred to work on home-made experiments. He rebelled so strongly against education in the classics that his family gave in, and at the age of seventeen he was sent to Rensselaer Technological Institute. He graduated in 1870 as a civil engineer and after two years in unsatisfactory jobs returned to Rensselaer as instructor in natural philosophy.

Whatever time he could spare from teaching he spent in research on magnetic permeability. His report on his work was rejected by the American Journal of Science, so he sent it to James Maxwell in Britain; Maxwell, impressed, had it published in London in the Philosophical Magazine. Few people in the United States noticed the paper. Rowland grew increasingly disgusted with his situation at Rensselaer and with the difficulties of physics research in America generally. Later, in 1883, he told a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, "I here assert that all can find time for scientific research if they desire it. But here, again, that curse of our country, mediocrity, is upon us. Our colleges and universities seldom call for first-class men of reputation, and I have even heard the trustee of a well-known college assert that no professor should engage in research because of the time wasted."

Rowland's quest for a place to do research ended suddenly in 1875 when he met Daniel Coit Gilman. Gilman was assembling a faculty for the newly endowed Johns Hopkins University, which was to be America's first true research institution, complete with graduate students, on the German model. Rowland joined happily and was sent on a tour of Europe to study laboratories and buy instruments. At Helmoltz's laboratory in Berlin, Rowland (like Michelson five years later) paused to perform a fundamental experiment which he had conceived earlier but had lacked the means to perform. This was a search for the magnetic effect of a charged rotating disc, a matter of considerable interest at a time when Maxwell's equations were the subject of vigorous debate. The experiment was difficult in the extreme, demanding extensive mathematical calculations as well as measurements at the edge of detectability, but Rowland carried it off. His work, the first demonstration that a charged body in motion produces a magnetic field, attracted much attention.

Rowland returned to Johns Hopkins with one of the finest collections of research instruments in the world. At the university he gave as little attention as possible to administration and teaching. To his students and colleagues he was often a forbidding figure, intolerant of mediocrity, so devoted to the truth that his frank criticism could be devastating. He spent most of the 1870's and 1880's in his laboratory turning out a remarkably varied and competent series of researches.

Although he was a capable mathematician and did some work on electromagnetic theory, Rowland's true genius was for experiment. He determined authoritatively the absolute value of the Ohm, the ratio of electrical units, the mechanical equivalent of heat, and the variation (which he was the first to demonstrate) of the specific heat of water with temperature. He also suggested and supervised the experiments which led one of his graduate students to the discovery of the Hall effect. But his greatest contribution to science was the construction of diffraction gratings, begun in 1882. Rowland's gratings were more than an order of magnitude larger and more accurate than any previous ones. He also discovered the peculiar advantages of ruling a grating on a concave surface. He sold hundreds of his plane and concave gratings at cost, and for a generation they were the foundation of physical, chemical and astronomical spectroscopy around the world. Rowland himself used his gratings to prepare a classic map of the solar spectrum.

Rowland married in 1890 and soon after learned that he was dying of diabetes. To provide for his family he devoted himself to inventing and patenting improvements in telegraphy. He wished to leave something for physics, too, and towards his death he was one of the principal founders and first president of The American Physical Society.

Rather than give one of Rowland's many excellent and elaborate scientific papers, we have chosen his description of the simple mechanical device with which he revolutionized spectroscopy, from the Encyclopedia Brittanica (9th ed., p. 552-53, reprinted here from The Physical Papers of Henry Rowland, 1902). We also give his famous address to The American Physical Society, reproduced from the first number of the Society's Bulletin (1899). It presents an overview of physics on the eve of the revolutions of quantum mechanics and relativity, and also gives an overview of the physicist himself. Today Rowland's image may seem almost arrogant in its elitism—but it was such feelings that raised American physics to a high professional level.