|

TENDENCY TO ROMANTICIZE HER OWN LIFE characterized Marie Curie

from girlhood on. In letters she wrote as a teenager she sometimes

presented herself as a tragic heroine. Similarly, in her 1923 biography

Pierre Curie and in the autobiographical notes appended to

it, she depicted herself and her husband as participants in a heroic

struggle. According to the self-portrait she propagated, Pierre and

Marie Curie, in their pursuit of scientific truth, had to overcome

not only poverty but also the indifference and even hostility of the

French establishment.

TENDENCY TO ROMANTICIZE HER OWN LIFE characterized Marie Curie

from girlhood on. In letters she wrote as a teenager she sometimes

presented herself as a tragic heroine. Similarly, in her 1923 biography

Pierre Curie and in the autobiographical notes appended to

it, she depicted herself and her husband as participants in a heroic

struggle. According to the self-portrait she propagated, Pierre and

Marie Curie, in their pursuit of scientific truth, had to overcome

not only poverty but also the indifference and even hostility of the

French establishment.

“My plans for the future? I have none....I mean to

get through as well as I can, and when I can do no more,

say farewell to this base world. The loss will be small,

and regret for me will be short....” --letter

of Marie Curie to her cousin Henrietta Michalowska, December

1886

|

|

|

| The romantic--and only

partially true--legend that Curie helped create of her heroic

early struggle was further spread by the 1943 film Madame

Curie, starring Greer Garson. |

|

|

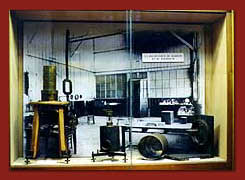

| The facilities in the School

of Industrial Physics and Chemistry shed, a model of which is

shown here, were barely adequate, but the Curies also had the

use of lab space, raw materials, and personnel provided by industrialists.

|

|

|

While not actually

false, this image of herself and Pierre as solitary laborers in

search of knowledge is only part of the truth. For example, in her

biography Pierre Curie, Marie devotes paragraphs to describing

the miserable old shed in which she and Pierre made their significant

discoveries. What she does not tell the reader is that from early

on in their work the Curies received significant assistance from

collaborators in industry. For example, the gross treatment of the

first ton of pitchblende, donated to the Curies by the Austrian

government, was performed in the factory of the Central Chemical

Products Company, which marketed Pierre's scientific instruments.

Far from laboring entirely on their own, the Curies were allied

with the French radioelements industry that their research did so

much to develop.

As for government

research grants and salaries, Marie and Pierre were treated as well

as most good scientists of their day. The real problem, Marie and

her friends insisted, was that science as a whole got far too little

funding.

“There

was no question of obtaining the needed proper apparatus

in common use by chemists....Sometimes I had to spend a

whole day mixing a boiling mass with a heavy iron rod nearly

as large as myself. I would be broken with fatigue at the

day's end.” --Marie Curie, Autobiographical

Notes

|

The romantic image

of the struggling scientist had already been established a generation

earlier by Louis Pasteur and others. While reflecting real difficulties,

the image also served as a propaganda tool. At a time when Curie

hoped to secure funding for her Radium Institute, her emphasis on

the difficulties she faced as a scientist helped not only to arouse

public sympathy but also to raise significant philanthropic donations

and put pressure on the French government. If more money could be

won for basic research by emphasizing certain aspects of her past

and downplaying others, a larger truth would be served--scientists

everywhere could do far more for humanity if they had better funding.

“All civilized groups,” Marie wrote, “have an absolute

duty to watch over the domain of pure science...and to provide [its

workers] with the support they need.”

� 2000 -

American Institute of Physics |

|