|

| “The Race for Radium.”

The public was fascinated by radium. In cheap science fiction

novels--and sometimes in sober newspaper articles--it was touted

as a magical substance whose rays could cure all ills, power

wondrous machines, or destroy a city at one blow. (Photo ACJC) |

|

|

|

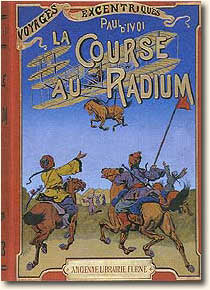

“Radium Salts/Polonium - Actinium/and

other radioactive substances.” An announcement and price

list for materials produced by Armet de Lisle's factory. Although

fabulously expensive, the materials were much in demand for

attacking cancer, skin diseases and other ailments. (Photo

ACJC)

READ

Curie's words

|

|

|

THRIVING INDUSTRY based on the “miracle” drug radium

soon grew up, however, and it was tightly linked with the Curies.

Pierre's pioneering work on the effects of radium on living organisms

showed it could damage tissue, and this discovery was put to use against cancer

and other ills. In 1904 French industrialist Armet de Lisle, whose

factory would soon provide radium to the medical profession, began

to collaborate with the Curies. De Lisle benefitted from the Curies'

technical suggestions on the best treatments for pitchblende. In

return the Curies were able to accumulate larger samples of radioactive

material than they would have been able to prepare on their own.

At a time when few research posts were available in France, de Lisle

also provided jobs in the new radium industry for a number of scientists

who had trained with the Curies.

THRIVING INDUSTRY based on the “miracle” drug radium

soon grew up, however, and it was tightly linked with the Curies.

Pierre's pioneering work on the effects of radium on living organisms

showed it could damage tissue, and this discovery was put to use against cancer

and other ills. In 1904 French industrialist Armet de Lisle, whose

factory would soon provide radium to the medical profession, began

to collaborate with the Curies. De Lisle benefitted from the Curies'

technical suggestions on the best treatments for pitchblende. In

return the Curies were able to accumulate larger samples of radioactive

material than they would have been able to prepare on their own.

At a time when few research posts were available in France, de Lisle

also provided jobs in the new radium industry for a number of scientists

who had trained with the Curies.

Although their collaboration

with industry advanced their scientific endeavors, the Curies did

not grow wealthy as a result. With a child and a parent to support,

household help to pay for, and an expensive research project to

carry out, Pierre sought a job with better pay. The product of an

unorthodox educational background, he found no welcome at French

universities.

“...we

were forced to recognize, toward 1900, that some increase

in our income was indispensable.”

|

|

| Then the

University of Geneva made an offer that included not only a good salary

but also an adequate private lab in which Marie would play an official

role. The threat of losing Pierre to Switzerland energized the French

establishment. Thanks to the intervention of French mathematician

Henri Poincaré, Pierre got the chair of physics in a Sorbonne program

that introduced medical students to the basics of physics, chemistry,

and natural history (and thus called PCN). |

|

| Henri Poincaré was one of

the senior scientists who admired the Curies' work, and steered

jobs and monetary awards their way. |

|

|

| Irène points to her mother's

radiation-scarred fingertips (Photo ACJC) |

|

New

Responsibilities and Concerns

New

Responsibilities and Concerns

O

LAB WAS PROVIDED with Pierre's PCN position, so the Curies maintained

their lab at the shed. Although Pierre's salary rose, his teaching

load doubled, since he kept his position at the Municipal School

also. The Curies noted the subsequent deterioration in his health.

They failed to consider a possible link between Pierre's attacks

of severe pain and the intense radiation they were working with.

Marie herself had lost nearly 20 pounds while doing her thesis research,

and both Curies did permanent damage to their fingertips from their

unprotected exposure to highly radioactive materials. O

LAB WAS PROVIDED with Pierre's PCN position, so the Curies maintained

their lab at the shed. Although Pierre's salary rose, his teaching

load doubled, since he kept his position at the Municipal School

also. The Curies noted the subsequent deterioration in his health.

They failed to consider a possible link between Pierre's attacks

of severe pain and the intense radiation they were working with.

Marie herself had lost nearly 20 pounds while doing her thesis research,

and both Curies did permanent damage to their fingertips from their

unprotected exposure to highly radioactive materials.

|

| Anxious

to contribute to the family income, Marie became the first woman to

be appointed lecturer at France's best teachers' training institution

for women. Located in the Paris suburb of Sèvres, the school had a

distinguished group of professors from the Sorbonne and elsewhere.

Marie was the first instructor there to include laboratory work in

the physics curriculum. |

|

| It took Curie, shown here

with some of her students at the Sèvres college for teachers,

a full year to figure out the appropriate level for effective

teaching. (Photo ACJC) |

|

“I

had to give much time to the preparation of my lectures

at Sèvres, and to the organization of the laboratory work

there, which I found very insufficient.”

|

EALTH

AND FINANCIAL CONCERNS were not the only problems to plague

the Curies as Marie wound up her thesis research. Although in the

course of her thesis work the prestigious French Academy of Sciences

had recognized Marie's scientific promise by awarding her a prize

on three occasions--and such prizes could be a significant source

of income for researchers--the academy dealt the Curies a blow by

denying membership to Pierre in 1902. At about the same time Marie's

beloved father died in Poland following a difficult gall bladder

operation. EALTH

AND FINANCIAL CONCERNS were not the only problems to plague

the Curies as Marie wound up her thesis research. Although in the

course of her thesis work the prestigious French Academy of Sciences

had recognized Marie's scientific promise by awarding her a prize

on three occasions--and such prizes could be a significant source

of income for researchers--the academy dealt the Curies a blow by

denying membership to Pierre in 1902. At about the same time Marie's

beloved father died in Poland following a difficult gall bladder

operation.

� 2000 -

American Institute of Physics

|

|