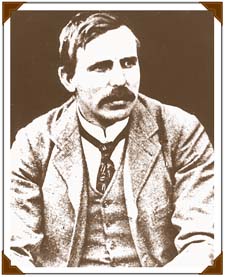

J.J. Thomson at

home in his

study in 1899.

|

"At first there were very few who believed in the existence of these bodies smaller than atoms."

|

|

homson presented three hypotheses about cathode rays based on his 1897 experiments: homson presented three hypotheses about cathode rays based on his 1897 experiments:

- Cathode rays are charged particles (which he called "corpuscles").

- These corpuscles are constituents of the atom.

- These corpuscles are the only constituents of the atom.

HEAR J.J. THOMSON talk about the size of the electron. HEAR J.J. THOMSON talk about the size of the electron.

homson's speculations met with some skepticism. The second and third hypotheses were especially controversial (the third hypothesis indeed turned out to be false). Years later he recalled, "At first there were very few who believed in the existence of these bodies smaller than atoms. I was even told long afterwards by a distinguished physicist who had been present at my lecture at the Royal Institution that he thought I had been 'pulling their legs.'" homson's speculations met with some skepticism. The second and third hypotheses were especially controversial (the third hypothesis indeed turned out to be false). Years later he recalled, "At first there were very few who believed in the existence of these bodies smaller than atoms. I was even told long afterwards by a distinguished physicist who had been present at my lecture at the Royal Institution that he thought I had been 'pulling their legs.'"

|

|

Joseph Larmor

|

he word "electron," coined by G. Johnstone Stoney in 1891, had been used to denote the unit of charge found in experiments

that passed electric current through chemicals. In this sense

the term was used by Joseph Larmor, J.J. Thomson's Cambridge

classmate. Larmor devised a theory of the electron that

described it as a structure in the ether (the invisible elastic

fluid that was proposed as a substrate for light and other

electrical phenomena). But Larmor's theory did not describe the

electron as a part of the atom. When the Irish physicist George

Francis FitzGerald suggested in 1897 that Thomson's corpuscles

were really "free electrons," he was actually disagreeing

with Thomson's hypotheses. FitzGerald had in mind the kind of

"electron" described by Larmor's theory. he word "electron," coined by G. Johnstone Stoney in 1891, had been used to denote the unit of charge found in experiments

that passed electric current through chemicals. In this sense

the term was used by Joseph Larmor, J.J. Thomson's Cambridge

classmate. Larmor devised a theory of the electron that

described it as a structure in the ether (the invisible elastic

fluid that was proposed as a substrate for light and other

electrical phenomena). But Larmor's theory did not describe the

electron as a part of the atom. When the Irish physicist George

Francis FitzGerald suggested in 1897 that Thomson's corpuscles

were really "free electrons," he was actually disagreeing

with Thomson's hypotheses. FitzGerald had in mind the kind of

"electron" described by Larmor's theory.

radually scientists accepted Thomson's first and second hypotheses, although with some subtle changes in their meaning. Experiments by Thomson, Lenard, and others through the crucial year of 1897 were not enough to settle the uncertainties. Real understanding required many more experiments over later

years. radually scientists accepted Thomson's first and second hypotheses, although with some subtle changes in their meaning. Experiments by Thomson, Lenard, and others through the crucial year of 1897 were not enough to settle the uncertainties. Real understanding required many more experiments over later

years.

|

Ernest Rutherford

|

heories about the atom proliferated in the wake of Thomson's 1897 work. If Thomson had found the single building block of all atoms, how could atoms be built up out of these corpuscles? Thomson proposed a model, sometimes called the "plum pudding" or "raisin cake" model, in which thousands of tiny, negatively charged corpuscles swarm inside a sort of cloud of massless positive charge. This theory was struck down by Thomson's own former student, Ernest Rutherford. Using a

different kind of particle beam, Rutherford found evidence that

the atom has a small core, a nucleus. Rutherford suggested that

the atom might resemble a tiny solar system, with a massive,

positively charged center circled by only a few electrons.

Later this nucleus was found to be built of new kinds of

particles (protons and neutrons), much heavier than

electrons. heories about the atom proliferated in the wake of Thomson's 1897 work. If Thomson had found the single building block of all atoms, how could atoms be built up out of these corpuscles? Thomson proposed a model, sometimes called the "plum pudding" or "raisin cake" model, in which thousands of tiny, negatively charged corpuscles swarm inside a sort of cloud of massless positive charge. This theory was struck down by Thomson's own former student, Ernest Rutherford. Using a

different kind of particle beam, Rutherford found evidence that

the atom has a small core, a nucleus. Rutherford suggested that

the atom might resemble a tiny solar system, with a massive,

positively charged center circled by only a few electrons.

Later this nucleus was found to be built of new kinds of

particles (protons and neutrons), much heavier than

electrons.

|

|

|

Table of Contents:

Exhibit Home

J.J. Thomson

Mysterious Rays

1897 Experiments

Corpuscles to Electrons

Legacy for Today

More Info

|

Legacy for Today Legacy for Today

|